Unlock newspaper knowledge with CrossAsia’s AI Explorer: explore and test two new features for finding similar and possibly relevant articles across languages

The defining characteristics of newspapers are timeliness (prompt reporting on current events), periodicity (regular publication), publicity (public dissemination of information accessible to everyone) and universality (broad thematic diversity ranging from politics to culture).

But what happens when we overcome language barriers and connect newspapers and news from different countries and languages? With the CrossAsia Newspaper Explorer, we can use technology to find similar and relevant articles across languages and scripts.

We added two new AI-powered features to the CrossAsia Newspaper Explorer one is and extension to the result sets you produced by one or combined search terms from one or more sources and will “Show results by similarity”, the other starts from one of the actual titles in your result set and triggers a “Cross-language search for similar titles.” These functions use vectors embeddings*, an advanced AI technique that captures the meaning of a text beyond individual words in that text and across different languages. No worries, you do not need to understand the underlying math, just be aware of that much: each text is transformed into a matrix of numbers describing the “meanings/concepts” in a text as a vector of a certain length and angle. Considered as “similar” are texts where length and angle of these “meanings” are close. Each text is described by hundreds of these vectors in a multi-dimensional space and to actually calculate closeness and display this in a 3D space the data is reduced in complexity.

We used stsb-xlm-r-multilingual (Ollama backend) to prepare the texts for this feature, for the display of the spatial relation and some other features we use Embedding Projector.

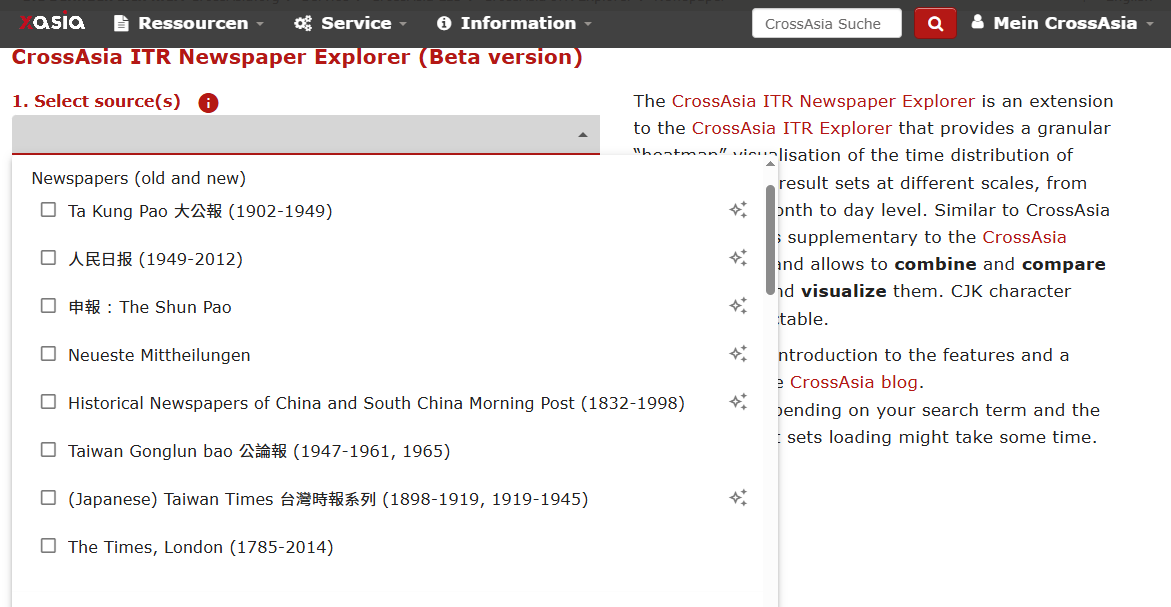

When selecting the “sources” for your search in the CrossAsia Newspaper Explorer, you will now notice a star icon![]() next to some data sources. This indicates that the source not only has a “word” index but in addition has been fully converted into embedding vectors and support the new features (fig.1).

next to some data sources. This indicates that the source not only has a “word” index but in addition has been fully converted into embedding vectors and support the new features (fig.1).

*Note: Embedding vectors are numerical representations created by AI to understand and compare the meaning of text, even in different languages. For a more extensive explanation please see here: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/vector-embedding

Sounds too abstract? Let’s look at an example.

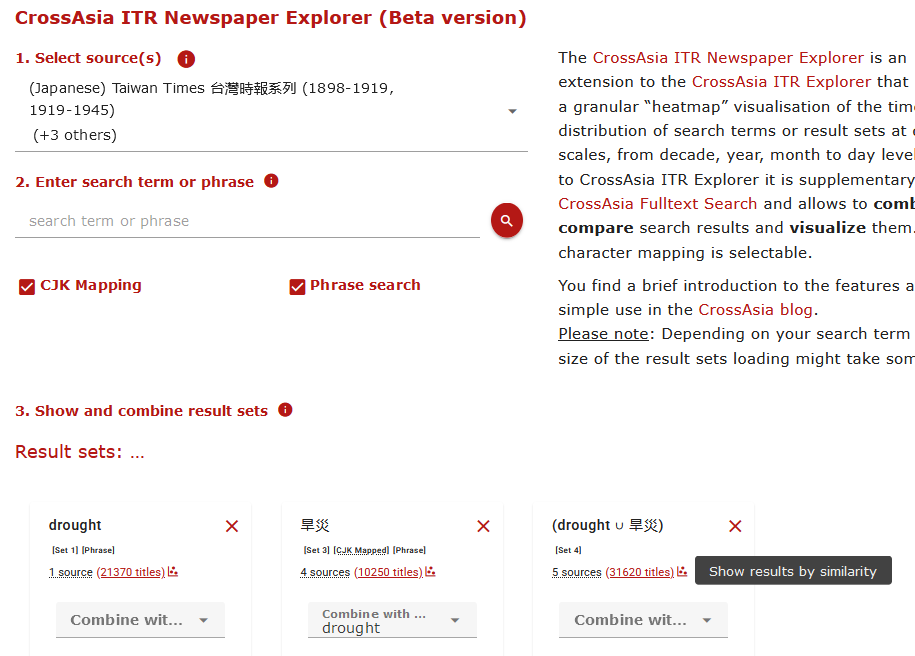

Every analysis in the ITR Explorer or Newspaper Explorer starts with producing result sets, i.e. searching for terms in sources, and – maybe – combining the result sets by OR, AND, or NOT. Our showcase example is a combination with OR of a search for 旱災 (“drought” in Chinese) across selected Chinese and Japanese newspaper sources (with CJK Mapping enabled) plus a search for the word drought in English newspapers published in China: drought ∪ 旱災 (fig.2).

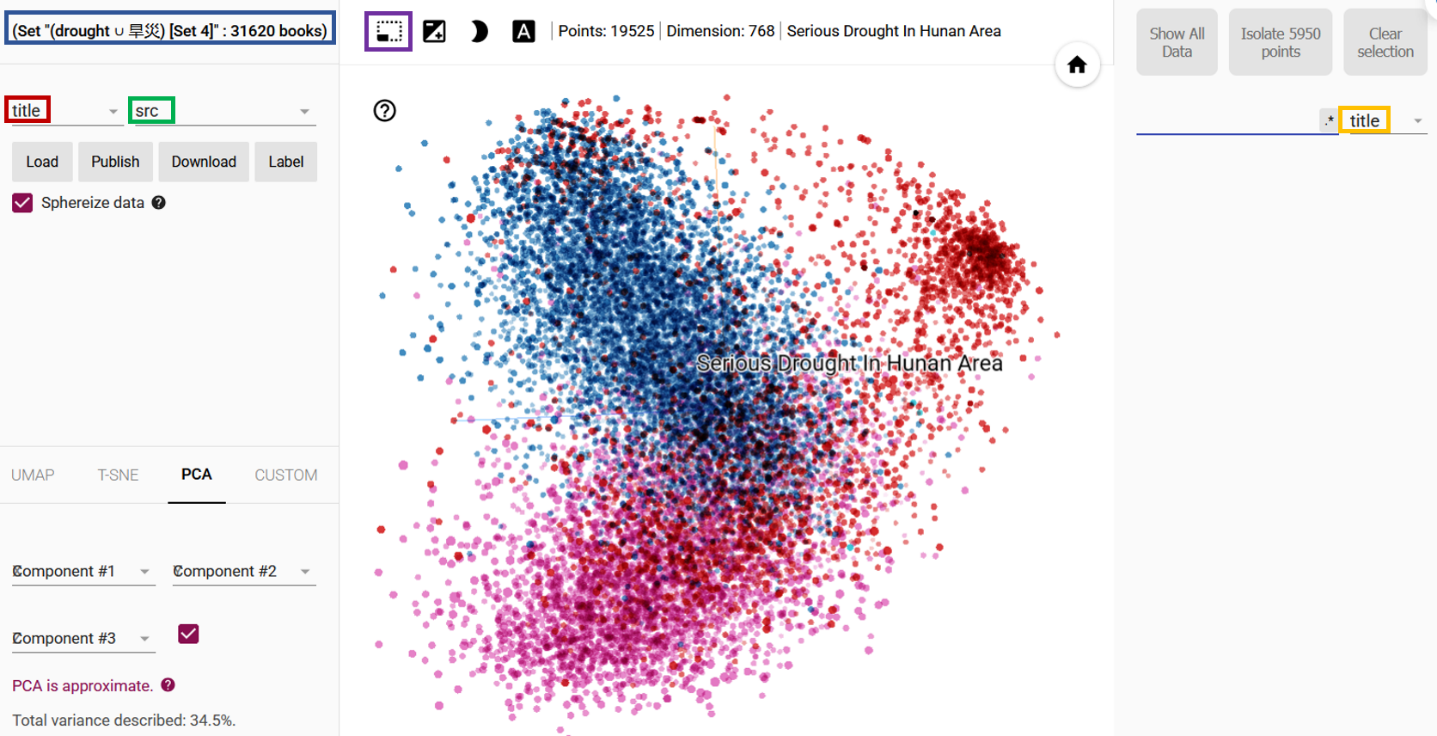

Clicking the icon in the combined result set will trigger the “Show results by similarity” function which loads all AI-based embedding vectors of the articles in the result set to the display and analysis tool Embedding Projector that will show semantically similar content across languages as a distribution with different distances and angles in a 3D space defined by the used AI model.

The Embedding Projector interface consists of three main sections:

- Left Panel: Shows the name and size of the loaded result set (blue frame), controls how the data points (dots) are labeled (red frame) and colored (green frame). This is the default setting. Titles appear on hover, colors reflect different data sources (src), and PCA is used for projection. Other available option for projection are UMAP and t-SNE. The “?” next to the projection gives an introduction how to use and interpret the projection.

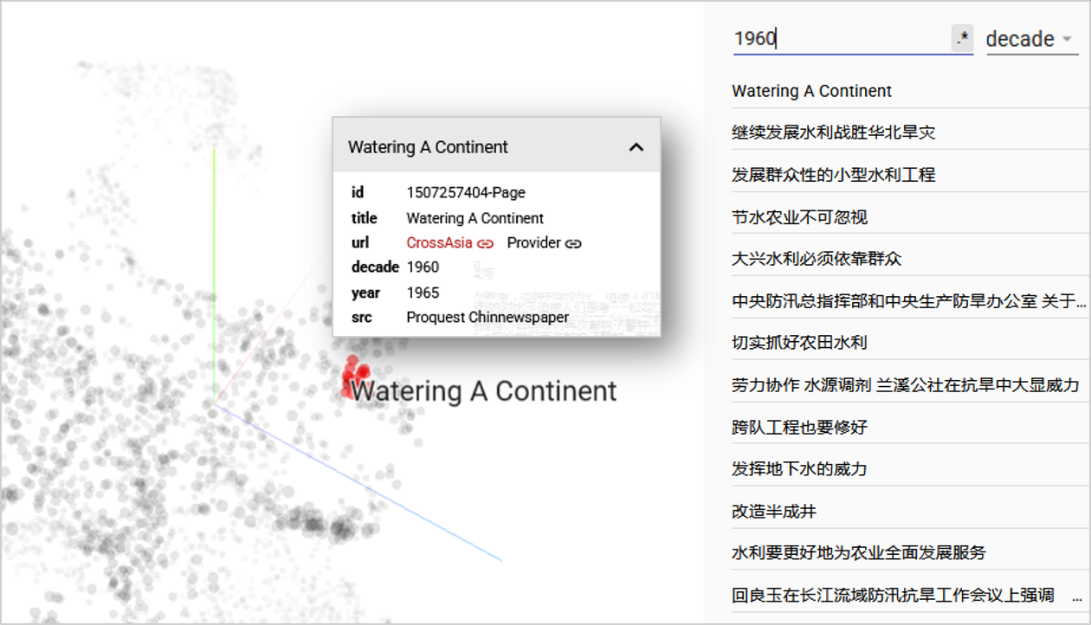

- Center Panel: Displays the interactive embedding viewer. You can zoom, rotate, and explore the data visually. A click on a dot opens a pop-up box with some basis metadata and CrossAsia link (in red) and Provider link (in black, for users with another IP access authentication) leading directly to the article in the provider’s database.

- Right Panel: When clicking on one dot/title in the center panel, similar records are highlighted and the right panel with their distance, title, and direct link to their database. It is also possible to display only data points that match certain metadata criteria, such as containing a certain term or being published in the 1960ies (fig. 4).

Fig.4: Filtering the data points by metadata, here those of the 1960ies and showing the pop-up box for selected article.

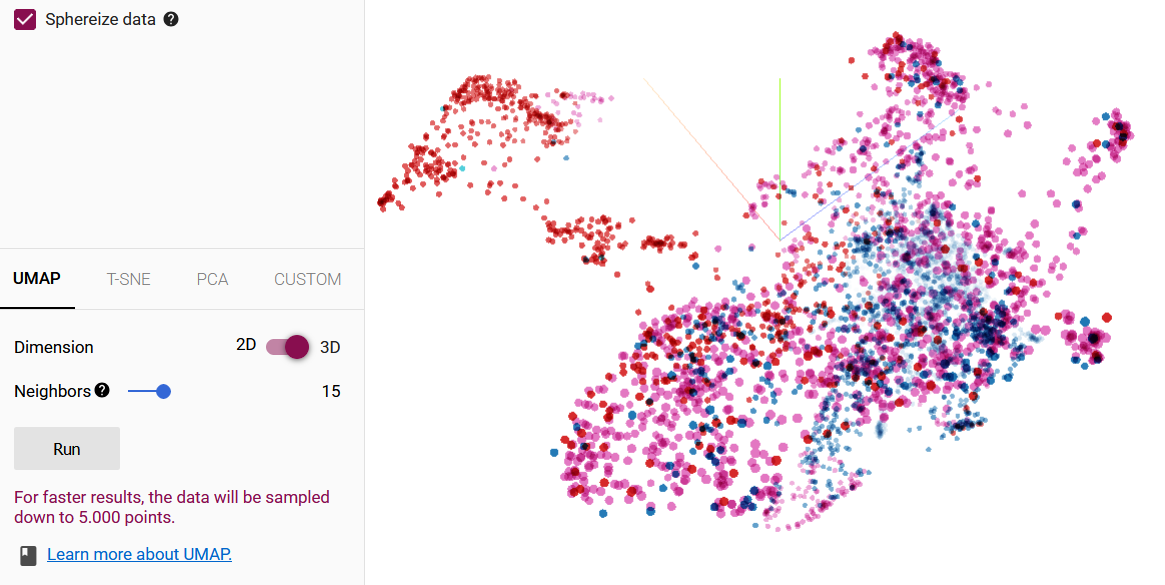

In the next screenshot (fig.5), the same result set uses UMAP to project the records.

Let’s explore the cluster of records in the upper middle where blue (English), pink and red (Chinese from RMRB and Dagong bao) titles mix by drawing a box (see fig. 3, lilac framed icon) around that cluster. The selection suggests that the articles are “similar” because “water management/水利” play a central role in them.

![]() “Cross-language search for similar titles”

“Cross-language search for similar titles”

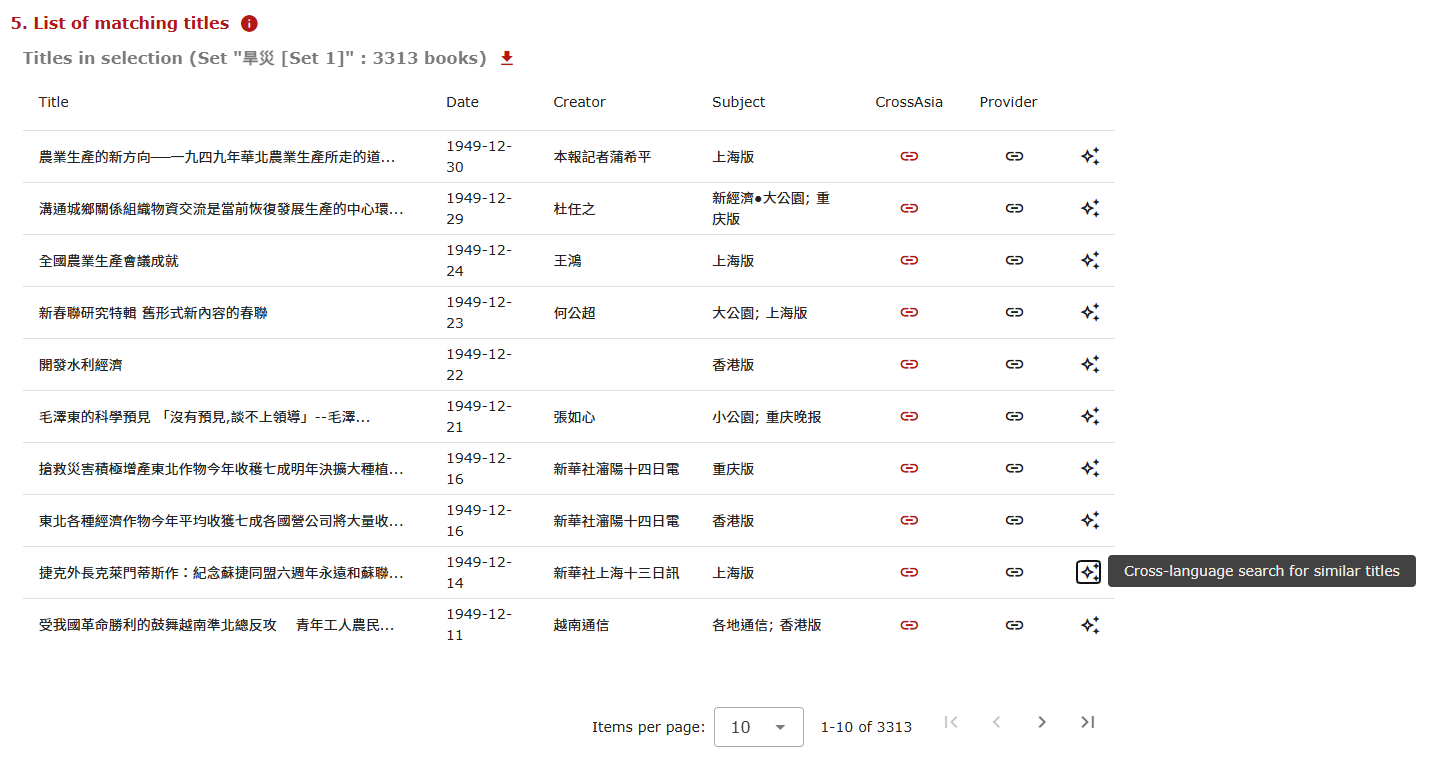

The second new feature of the CrossAsia ITR Newspaper Explorer is an addition to the fifth section in the ITR Explorer interface: “List of matching titles”. This function has the same features as the one described above, but displays not a pre-defined set of titles, but starts from one specific article within the result set to then search for similar titles across all data sources in which this AI feature is enabled. A click on the star icon next to one of the titles will trigger the search and display (fig. 7).

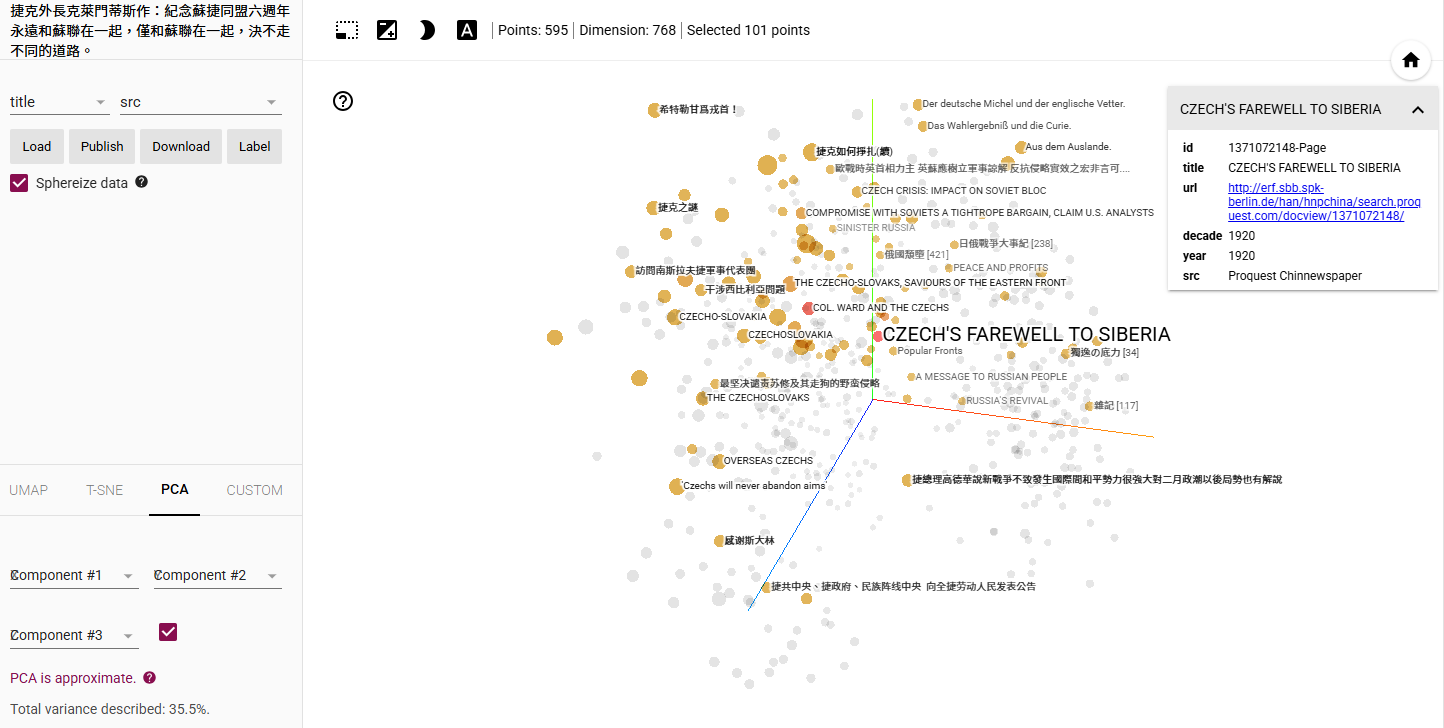

Starting from the Chinese article “捷克外長克萊門蒂斯作:紀念蘇捷同盟六週年永遠和蘇聯” (Czech Foreign Minister Clementis: Commemorating the Sixth Anniversary of the Soviet-Czech Alliance, Forever with the Soviet Union) the AI search will find “similar titles” also in other languages than Chinese such as the English newspaper article “CZECH’S FAREWELL TO SIBERIA” (fig. 8).

Fig.8: Display of result of a Chinese article will also show English articles that are considered similar in “meaning”

No tool makes sense without users!

Please share your experiences when using the new ITR Newspaper feature with us and the community. Have you found interesting and un-expected but useful results using this feature? Have you advised for other users how to best proceed making best use it? Please share as comments to this blog. Thank you!

The new features are – as are all CrossAsia Lab tools – open to all users and not confined to those being able to access the licensed databases. If you find flaws or errors or have suggestions for improvement, do not hesitate to contact us via the x-asia address or use the comment function in the CrossAsia Forum.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – PK, Bandō-Sammlung, Depositum des Deutschen Instituts für Japanstudien, Signatur H 52

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – PK, Bandō-Sammlung, Depositum des Deutschen Instituts für Japanstudien, Signatur H 52