Gastbeitrag von Dr. Thies Staack (Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures, University of Hamburg)

(Die deutschsprachige Version finden Sie im Stabi-Blog)

During the past few years, I have been conducting a research project on the collecting and exchange of medical recipes in 19th and early 20th century China at the Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures (CSMC) in Hamburg. Since manuscripts, both bound recipe books and individual recipes on loose leaves, played an important role in this respect, the Unschuld collection of Chinese medical manuscripts is an invaluable source for my research.

Among the close to 1,000 manuscripts from the Unschuld collection now housed at the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin Preußischer Kulturbesitz (SBB-PK), there is a small thread-bound volume with an inconspicuous outside appearance but an extraordinarily rich content of overall roughly 800 mostly medical recipes. The manuscript with the shelf mark “Slg. Unschuld 8051” was produced in 19th century Canton and attests to a vibrant exchange of medical recipes during that period. I have introduced it in some more detail elsewhere. According to the description in the catalogue of the collection, published by Paul U. Unschuld and Zheng Jinsheng in 2012, the manuscript does not have an original title, which would usually be found on the front cover or on the first page of a volume. The title provided in the catalogue – Yifang jichao 醫方集抄 or “Hand-copied collection of medical formulas” – was obviously assigned by Unschuld and Zheng based on its content.

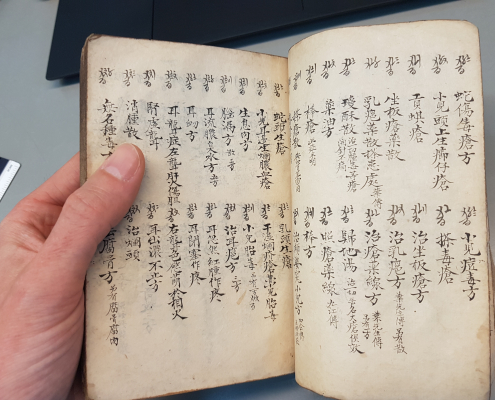

Fig. 1: Slg. Unschuld 8051, opened at the table of contents (photo by the author).

The fact that Slg. Unschuld 8051, like many other manuscripts from the Unschuld collection, has already been digitised is of tremendous help for my research. Still, to be able to thoroughly assess the materiality of this written artefact, for example, to get a feel for its size and weight, I went to Berlin to inspect Slg. Unschuld 8051 in the SBB reading room in April 2022. The first surprise was just how small and portable the volume is (see Fig. 1). It would easily fit into a pocket or sleeve and the stains on its covers suggest that it may indeed have been carried around a lot by its previous owners.

Fig. 2: The bottom edge of Slg. Unschuld 8051 under normal interior light (photo by the author).

When I turned the manuscript in my hands, I noticed what appeared to be writing with ink on the bottom of the volume (see Fig. 2). For some of the thread-bound Unschuld manuscripts images of the top, front and bottom edge as well as the spine have been included in the digitised version. This is, unfortunately, not the case for Slg. Unschuld 8051, which was digitised already in 2014. Hence, this was the first time I got to see the bottom edge of the manuscript. Due to the darkening of the paper at the edges, it was difficult to decipher any writing, but fortunately I had brought a portable digital microscope (Dino-Lite) from Hamburg, which allows analysis with the help of light in the invisible spectrum (ultraviolet and infrared light).

Carbon ink, which was traditionally used in China, is much more clearly visible under infrared light than it is under daylight. The infrared images taken with the Dino-Lite showed clearly discernible brushstrokes (see Fig. 3). Since the area that can be photographed with the microscope’s magnification is rather small, I had to piece together several images to be able to decipher whole characters (see Fig. 4), but this was sufficient to ascertain the presence of writing.

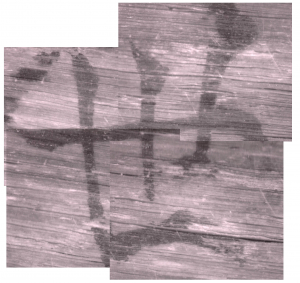

Fig. 3: One of the infrared images taken with the help of the Dino-Lite microscope (photo by the author).

Fig. 4: Combination of four Dino-Lite infrared images, together showing the character 世, with the help of image processing software (processed image by the author).

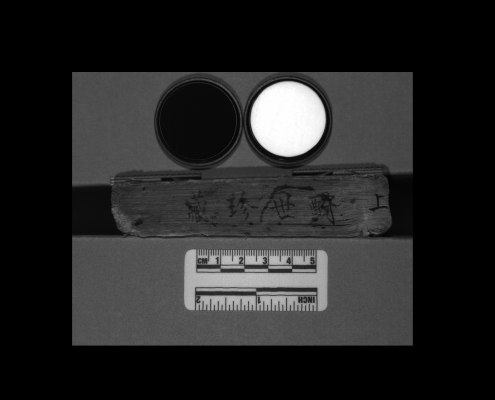

Fig. 5: Setup of the Opus Apollo infrared reflectography (IRR) camera above Slg. Unschuld 8051 in the Berlin State Library storage (photo by the author).

In order to acquire a high-quality infrared image of the whole bottom edge, my colleagues Ivan Shevchuk, Kyle Ann Huskin and Dr. Olivier Bonnerot from the CSMC helped me capture images with a professional infrared reflectography (IRR) camera (Opus Apollo) in September 2022 (see Fig. 5). Finally, it was possible to decipher the entire inscription of five characters (see Fig. 6).

The four larger characters, which must be read choushi zhencang 酧世珍藏, from right to left, on first sight resemble a typical ownership mark of a book collector. The expression zhencang 珍藏 “treasured collection (of)” together with a personal name could constitute a statement of ownership. However, book collectors more commonly used a seal stamp and red ink to apply their ownership mark. The fifth character in slightly smaller script to the very right (shang 上) hints towards the possibility that what we have here might rather be the title of the present recipe collection. Since the table of contents at the beginning of Slg. Unschuld 8051 lists recipes in a “first volume” (shang juan 上卷) and a “second volume” (xia juan 下卷), it is clear that the recipe collection comprised overall two volumes. Comparison with the actual recipe entries shows that the present volume is indeed the first of the two, which accords well with the small character written on the bottom edge. It is also worth pointing out that traditional thread-bound books – whether handwritten or printed – often had their title inscribed on their bottom edge in addition to the cover or title page. The reason for this is a common way of storage, with books being shelved lying flat on their back with the bottom edge facing towards the front. Hence, a title placed at this position is legible while the book is stored on a shelf, similar to the title on the spine of a “Western” book.

Fig. 6: Calibrated infrared reflectography (IRR) image of the bottom edge of Slg. Unschuld 8051 (photo by Olivier Bonnerot, Kyle Ann Huskin and Ivan Shevchuk).

If choushi zhencang 酧世珍藏 is in fact the title of this recipe book, it was probably selected by the compiler of the recipes for his personal collection. At least, this title is not found in the union catalogue of Chinese medical writings. The first two characters – with 酧 being a common variant of 酬 – seem to echo the title of the popular 19th c. household encyclopaedia Choushi jinnang 酬世錦囊 “Brocade Bag of Exchange with the World”, which provided guidance on etiquette and proper social interaction. As part of the title of a recipe collection, the expression “exchange with the world” could rather refer to the way in which the compiler got hold of the recipes, many of which are indeed noted as having been received from relatives, friends or acquaintances in Canton. Hence, it might be understood as “Treasured Collection of (Recipes obtained through) Exchange with the World”.

This example showcases not only the advantages of infrared reflectography, which can allow to decipher otherwise illegible writing on manuscripts. It also points to the fact that inclusion of images of all sides of a manuscript in its digital version – in the case of thread-bound volumes also the edges and the spine – would greatly benefit research. Nevertheless, it must be stressed that even this can never entirely replace a first-hand inspection of the original written artefact in the reading room.

The data set with infrared reflectography images of Slg. Unschuld 8051 has been published as:

Olivier Bonnerot, Kyle Ann Huskin, Ivan Shevchuk and Thies Staack (2025), Infrared Reflectography Images of the Writing on the Bottom Edge of Slg. Unschuld 8051, http://doi.org/10.25592/uhhfdm.16994.

Acknowledgements:

The author thanks Dr. Cordula Gumbrecht and Dr. Andreas Janke for valuable suggestions on an earlier draft of the text.

The research behind this contribution was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy – EXC 2176 “Understanding Written Artefacts: Material, Interaction and Transmission in Manuscript Cultures”, project no. 390893796. The research was conducted within the scope of the Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures (CSMC) at the University of Hamburg.

Feature image:

Two pages from the table of contents of Slg. Unschuld 8051, showing the recipes at the end of the first and the beginning of the second volume. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – PK, Slg. Unschuld 8051, f. 23v-24r, scan pages [48]-[49] (Retrieved from http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB0000603200000048 and http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB0000603200000049)

Connecting Through Korean Studies: German Librarians at ENKRS 2025

/in Aktuelles, SBB/by Jing Hu(German translation below)

The 2025 workshop of the European Network of Korean Resources Specialists (ENKRS) took place from May 21 to 24 in Olomouc, Czech Republic, hosted by the Department of Asian Studies at Palacký University. This year’s theme, “Korean Studies Librarianship and Digital Humanities: Opportunities and Challenges for Librarians in Supporting the Next Generation of Korean Studies Scholars,” brought together specialists to share expertise and discuss the evolving role of librarians in the digital age.

Two colleagues from the Korea Section of the East Asia Department at the Berlin State Library, Mrs. Jing Hu and Mrs. Cherim Adelhoefer, participated in the event. During the pre-conference session on May 21, Mrs. Adelhoefer gave a presentation on cataloguing practices at the Berlin State Library, offering insights into workflows for Korean materials. She also engaged in lively exchanges with librarians from other countries on cataloguing standards and practices. In the main conference session on May 22, Mrs. Jing Hu presented an overview of digital scholarship initiatives within the East Asia Department, introducing services such as the N-gram service and the ITR (Integrated Text Repository) explorer. Her talk highlighted Stabi’s strategies for supporting digital research in East Asian Studies.

The workshop also served as a valuable networking platform, particularly for colleagues from Germany. In addition to Mrs. Hu and Mrs. Adelhoefer, three other librarians from Freie Universität Berlin, the University of Tübingen, and Heidelberg University attended the event. Together, they discussed shared challenges in Korean Studies librarianship and explored opportunities for future collaboration to address common tasks.

Founded in 2018, the ENKRS now has 99 members. Its inaugural workshop was held at Freie Universität Berlin in 2018. The network continues to grow, welcoming not only European librarians but also colleagues from the United States and South Korea. This year’s event brought together 49 participants from 13 countries. We look forward to next year’s ENKRS workshop – possibly in Berlin, and ideally at our Stabi – to the continued exchange of ideas and best practices in Korean Studies librarianship!

From left to right: Jing Hu (Stabi), Cherim Adelhoefer (Stabi), Annika Timmins (Universität Tübingen), Gesche Schröder (Heidelberg University); in the middle: Liliane Sperr (Freie Universität Berlin).

Vernetzung durch Koreanistik: Deutsche Bibliothekarinnen auf dem ENKRS-Workshop 2025

Der Workshop 2025 des European Network of Korean Resources Specialists (ENKRS) fand vom 21. bis 24. Mai in Olomouc, Tschechien, statt und wurde vom Lehrstuhl für Asienstudien der Palacký-Universität ausgerichtet. Das diesjährige Thema „Korean Studies Librarianship and Digital Humanities: Opportunities and Challenges for Librarians in Supporting the Next Generation of Korean Studies Scholars“ brachte Fachleute zusammen, um Wissen auszutauschen und über die sich wandelnde Rolle von Bibliothekar*innen im digitalen Zeitalter zu diskutieren.

Zwei Kolleginnen aus der Korea-Referat der Ostasienabteilung der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Frau Jing Hu und Frau Cherim Adelhoefer, nahmen an der Veranstaltung teil. Am 21. Mai, während der Vorkonferenz, hielt Frau Adelhoefer einen Vortrag über die Katalogisierungspraxis an der Stabi und gab Einblicke in die Arbeitsabläufe bei der Erschließung koreanischer Materialien. Zudem tauschte sie sich lebhaft mit Kolleg*innen aus anderen Ländern über Katalogisierungsstandards und -methoden aus. In der Hauptkonferenz am 22. Mai stellte Frau Jing Hu die digitalen Forschungsinitiativen der Ostasienabteilung vor. Dabei präsentierte sie unter anderem den N-Gram-Service und den ITR-Explorer (Integrated Text Repository). Ihr Vortrag beleuchtete Strategien der Stabi zur Unterstützung digitaler Forschung in den Ostasienstudien.

Der Workshop diente auch als wertvolle Plattform zur Vernetzung, insbesondere für Kolleginnen aus Deutschland. Neben Frau Hu und Frau Adelhoefer nahmen auch drei weitere Bibliothekarinnen von der Freien Universität Berlin, der Universität Tübingen und der Universität Heidelberg teil. Gemeinsam diskutierten sie über gemeinsame Herausforderungen im Bereich der koreanistischen Bibliotheksarbeit und loteten Kooperationsmöglichkeiten für zukünftige Projekte aus.

Das ENKRS wurde 2018 gegründet und zählt heute 99 Mitglieder. Der erste Workshop fand 2018 an der Freien Universität Berlin statt. Das Netzwerk wächst stetig weiter und begrüßt nicht nur europäische, sondern auch Kolleginnen aus den USA und Südkorea. In diesem Jahr nahmen 49 Teilnehmerinnen aus 13 Ländern an der Veranstaltung in Olomouc teil. Wir freuen uns bereits auf den nächsten ENKRS-Workshop – eventuell in Berlin, idealerweise bei uns in der Stabi – sowie auf den weiteren Austausch zu Ideen und Best Practices in koreanistischen Bibliotheksarbeit!

Wie klangen Buddhas Worte im Originalton? – Eine Tripitaka-Schenkung an die Staatsbibliothek

/in Aktuelles, Ausstellungen, Besuche, Sammlungen, SBB, Veranstaltungen/by Claudia Götze-SamCrossAsia Talks: Lukáš Kubík 05.05.2025

/in CrossAsia Stipendiaten, Newsletter 33, Veranstaltungen, Vortragsreihe "CrossAsia Talks"/by CrossAsia(See English below)

Nach seinem Aufenthalt in der Ostasienabteilung der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin im Rahmen des Stipendienprogramms der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz im Jahr 2024 hält Herr Lukáš Kubík (Karls-Universität, Prag) am 05.05.2025 ab 18 Uhr (Berliner Zeit) einen Onlinevortrag mit dem Thema “(Un)official Korean Sources on late Koryŏ in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin’s East Asian Collection”. In seinem Vortrag wird er die Erkenntnisse aus seiner Forschung in den Berliner Beständen zu historischen Quellen aus der späten Koryŏ-Zeit genauer vorstellen.

In this lecture, I will talk about Korean historical sources held in the East Asian collection of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, focusing on both official and unofficial narratives from the late Koryŏ period onward. While official histories document key events, a range of unofficial sources offers unique, often personal perspectives that enrich our understanding of the past. Among these are educational texts used in private academies, or Sŏwŏn (書院), which compile Korean history from earlier works to create accessible overviews for students. Equally significant are the Munjip (文集), or collected writings of scholars, officials, and literati, which capture personal reflections and experiences rarely found in state-sanctioned records. These various sources reveal a complex and multifaceted picture of Korea’s historical and intellectual traditions, allowing us to explore widely accepted accounts and individual viewpoints.

Die Vortragssprache ist Englisch. Bei Fragen kontaktieren Sie uns unter: ostasienabt@sbb.spk-berlin.de.

Der Vortrag wird via Webex gestreamt und aufgezeichnet*. Sie können am Vortrag über Ihren Browser ohne Installation einer Software teilnehmen. Klicken Sie dazu unten auf „Zum Vortrag“, folgen dem Link „Über Browser teilnehmen“ und geben Ihren Namen ein.

Alle bislang angekündigten Vorträge finden Sie hier. Die weiteren Termine kündigen wir in unserem Blog und auf unserem X-Account an.

Weitere Informationen zum Vortragsthema finden Sie im Gastbeitrag von Herrn Kubík zu seinem Forschungsaufenthalt an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Alle Informationen zum Stipendienprogramm der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz können Sie hier finden.

—

After his stay as part of the grant programme of the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Mr Lukáš Kubík (Charles University, Prague) will give an online lecture on 5 May 2025 from 6 pm (Berlin time) on the topic ‘(Un)official Korean Sources on late Koryŏ in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin’s East Asian Collection’. In his lecture, he will present the findings from his research in the Berlin holdings on historical sources from the late Koryŏ period in more detail.

In this lecture, I will talk about Korean historical sources held in the East Asian collection of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, focusing on both official and unofficial narratives from the late Koryŏ period onward. While official histories document key events, a range of unofficial sources offers unique, often personal perspectives that enrich our understanding of the past. Among these are educational texts used in private academies, or Sŏwŏn (書院), which compile Korean history from earlier works to create accessible overviews for students. Equally significant are the Munjip (文集), or collected writings of scholars, officials, and literati, which capture personal reflections and experiences rarely found in state-sanctioned records. These various sources reveal a complex and multifaceted picture of Korea’s historical and intellectual traditions, allowing us to explore widely accepted accounts and individual viewpoints.

The lecture will be held in English. If you have any questions, please contact us: ostasienabt@sbb.spk-berlin.de.

The lecture will be streamed and recorded via Webex*. You can take part in the lecture using your browser without having to install a special software. Please click on the respective button “To the lecture” below, follow the link “join via browser” (“über Browser teilnehmen”), and enter your name.

You can find all previously announced lectures here. We will announce further dates in our blog and on X.

Further information on the topic of the lecture can be found in Mr Kubík’s guest article on his research stay at the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. All inormation about the Grant program of the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz can be found here.

*Mit Ihrer Teilnahme an der Veranstaltung räumen Sie der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz und ihren nachgeordneten Einrichtungen kostenlos alle Nutzungsrechte an den Bildern/Videos ein, die während der Veranstaltung von Ihnen angefertigt wurden. Dies schließt auch die kommerzielle Nutzung ein. Diese Einverständniserklärung gilt räumlich und zeitlich unbeschränkt und für die Nutzung in allen Medien, sowohl für analoge als auch für digitale Verwendungen. Sie umfasst auch die Bildbearbeitung sowie die Verwendung der Bilder für Montagen. / By participating, you grant the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz and its subordinate institutions free of charge all rights of usage of pictures and videos taken of you during this lecture presentation. This declaration of consent is valid in terms of time and space without restrictions and for usage in all media, including analogue and digital usage. It includes image processing and the usage of photos in composite illustrations. German law will apply.

Classroomprogramm für das Sommersemester 2025 ist online

/in Aktuelles, E-Publishing, Schulungen/by Antje ZiemerLiebe Nutzer:innen,

pünktlich zum Beginn des Sommersemester 2025 steht Ihnen wieder ein umfangreiches Schulungsangebot im CrossAsia Classroom zu unseren hauseigenen Angeboten zur Verfügung! Wir bieten, wie in jedem Semester, Einführungsschulungen zu CrossAsia und den einzelnen Regionen (China, Japan, Korea, Südostasien und Zentralasien) sowie zu speziellen Themen und einzelnen Datenbanken an. Es wird auch wieder eine Schulung rund um das CrossAsia Repository stattfinden.

Die Schulungen beginnen am 28.04. mit einer allgemeinen Einführung zu CrossAsia. Das vollständige Programm finden Sie hier sowie unter der Rubrik „Wissenswerkstatt“ im Veranstaltungskalender der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin hier.

Auf der CrossAsia Classroom-Seite finden Sie außerdem aktuelles Infomaterial zu den einzelnen Regionen und Links zu unseren CrossAsia Tutorials.

Fall Sie als Institution ein auf Sie und ihr Publikum zugeschnittenes Web-Seminare kostenfrei buchen möchten, können Sie sich gerne über x-asia@sbb.spk-berlin.de mit uns in Verbindung setzen oder direkt unsere regionalen Referent:innen dahingehend kontaktieren.

****

Dear users,

Just in time for the start of the summer semester 2025, we are once again offering you a comprehensive range of training courses in the CrossAsia Classroom on our in-house services! As in every semester, we offer introductory training courses on CrossAsia and the individual regions (China, Japan, Korea, Southeast Asia and Central Asia) as well as on special topics and individual databases. There will also be another training course on the CrossAsia Repository.

The training courses will start on April 28th with a general introduction to CrossAsia. The full programme can be found here and under the heading ‘Wissenswerkstatt’ in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin’s calendar of events here.

On the CrossAsia Classroom page you will also find up-to-date information material on the individual regions and links to our CrossAsia tutorials.

If you are an institution and would like to book a web seminar tailored to you and your audience free of charge, please contact us at x-asia@sbb.spk-berlin.de or contact our regional subject specialists directly.

Neuer Datenbankzugang: Gale British Library Newspapers Part VII: Southeast Asia, 1806–1977

/in Aktuelle Testzugänge, Aktuelles/by Tristan HinkelWir freuen uns mitteilen zu können, dass CrossAsia nun den Zugang zur Datenbank Gale British Library Newspapers Part VII: Southeast Asia, 1806–1977 anbieten kann, deren Digitalisate aus den umfangreichen Beständen der British Library angefertigt wurden. Es handelt sich hierbei um den kürzlich veröffentlichten, siebten Teil der digitalen Sammlung British Library Newspapers, der 36 seltene englischsprachige Zeitungen und Zeitschriften umfasst, die auf dem Gebiet der heutigen Staaten Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapur und Thailand über einen Zeitraum von mehr als 170 Jahren – von den frühen 1800er Jahren bis in die späten 1970er Jahre – veröffentlicht wurden. Die Sammlung stellt eine unschätzbare Ressource zur Erforschung von Themen im Bereich Politik, Wirtschaft, Kultur und Gesellschaft des kolonialen und postkolonialen Südostasiens sowie der Geschichte von Journalismus und Verlagswesen im Allgemeinen dar. Sie enthält u.a. folgende Zeitungen:

6 Trials des taiwanischen Anbieters TBMC bis zum 31.05.2025

/in Aktuelle Testzugänge, Aktuelles/by Duncan PatersonLiebe CrossAsia Nutzenden,

wir haben bis zum 31.05.2025 Trials für folgende Datenbanken mit einem Limit von 50 Image per Datenbank:

Taiwan Times 臺灣時報 Taiwan JIHO 資料庫

Taiwan Times 臺灣時報 wurde während der japanischen Besatzung (1895–1945) vom taiwanesischen Gouverneurshaus als japanische Zeitschrift veröffentlicht und enthielt Artikel und statistisches Material aus vielen Bereichen. Die Datenbank deckt fast die gesamte Zeit der japanischen Besatzung ab und umfasst auch den Vorgängerbericht der Taiwan Association, 臺灣協會會報.

Link: http://erf.sbb.spk-berlin.de/han/tbmc-jiho/

Collected Documents on Taiwan 臺灣文獻匯刊

Die Sammlung umfasst über 600 Titel und Auszüge persönlicher Schriften sowie lokale historische Aufzeichnungen aus verschiedenen Bibliotheken, Archiven und zivilgesellschaftlichen Organisationen in Festlandchina, darunter eine große Anzahl bisher unveröffentlichter Exemplare, Manuskripte und seltener Ausgaben mit insgesamt rund 100 Millionen chinesischen Schriftzeichen.

Link: http://erf.sbb.spk-berlin.de/han/tbmc-hueikang/

Contemporary Taiwan Biographical Database 臺灣當代人物誌資料庫

Die Contemporary Taiwan Biographical Database (臺灣當代人物誌數據庫) ist eine Sammlung von über 100.000 Dateneinträgen zum Leben erfolgreicher Männer und Frauen von 1946 bis 1990.

Link: http://erf.sbb.spk-berlin.de/han/tbmc-ctbdb/

Taiwan Biographical Archive 臺灣人物誌資料庫

Taiwan Biographical Archive 臺灣人物誌數據庫 enthält biographische Daten zu historischen Figuren der Japanaischen Besastzungszeit und der späten Qing 1895 bis 1945.

Link: http://erf.sbb.spk-berlin.de/han/tbmc-tba/

Taiwan News Smart Web 台灣新聞智慧網

Taiwan News Smart Web bietet über 13 Millionen Schlagzeilen und 100 Wörter umfassende Abstracts von zehn großen taiwanesischen Zeitungen der United Daily News Group (seit 2001) und der China Times Group (seit 2003) mit täglichen Aktualisierungen von über 2.000 Datensätzen.

Link: http://erf.sbb.spk-berlin.de/han/tbmc-newsweb/

Central Daily News 中央日報全報影像資料庫

Die Central Daily News 中央日報全報影像 ist seit Jahren das offizielle Nachrichtenmedium der KMT-Regierung und die älteste chinesische Zeitung der Welt. Sie wurde erstmals im Februar 1928 in Shanghai veröffentlicht und 1949 nach Taiwan verlegt.

Link: http://erf.sbb.spk-berlin.de/han/tbmc-centraldaily/

Wir wünschen viel Spaß beim Stöbern, und freuen uns auf Feedback.

Ihr/Euer

CrossAsia Team

Dear CrossAsia users,

We added trials for the following databases until 2025-05-31 with a limit of 50 images per database:

Taiwan Times 臺灣時報 Taiwan JIHO 資料庫

Taiwan Times 臺灣時報 was published as a Japanese magazine by the Taiwanese Governor’s House during the Japanese occupation (1895–1945) and contained articles and statistical material from many fields. The database covers almost the entire period of Japanese occupation and also includes the Taiwan Association’s predecessor report, 臺灣協會會報.

Link: http://erf.sbb.spk-berlin.de/han/tbmc-jiho/

Collected Documents on Taiwan 臺灣文獻匯刊

The collection includes over 600 titles and excerpts of personal writings, as well as local historical records from various libraries, archives, and civil society organizations in mainland China, including a large number of previously unpublished copies, manuscripts, and even rare editions, totaling approximately 100 million Chinese characters.

Link: http://erf.sbb.spk-berlin.de/han/tbmc-hueikang/

Contemporary Taiwan Biographical Database 臺灣當代人物誌資料庫

The Contemporary Taiwan Biographical Database (Contemporary Taiwan Biographical Database) is a collection of over 100,000 data entries on the lives of successful men and women from 1946 to 1990.

Link: http://erf.sbb.spk-berlin.de/han/tbmc-ctbdb/

Taiwan Biographical Archive 臺灣人物誌資料庫

Taiwan Biographical Archive (Taiwan Biographical Archive) contains biographical data on historical figures from the Japanese occupation period and the late Qing 1895 to 1945.

Link: http://erf.sbb.spk-berlin.de/han/tbmc-tba/

Taiwan News Smart Web 台灣新聞智慧網

Taiwan News Smart Web offers over 13 million headlines and 100-word abstracts from ten major Taiwanese newspapers in the United Daily News Group (since 2001) and the China Times Group (since 2003), with daily updates of over 2,000 records.

Link: http://erf.sbb.spk-berlin.de/han/tbmc-newsweb/

Central Daily News 中央日報全報影像資料庫

Central Daily News 中央日報全報影像 has been the official news media for the KMT government for years, and is the oldest Chinese newspapers in the world. It was first published in Shanghai in February 1928 and later moved to Taiwan in 1949.

Link: http://erf.sbb.spk-berlin.de/han/tbmc-centraldaily/

We hope you enjoy browsing and look forward to your feedback.

Your

CrossAsia team

The Advantages of Infrared Reflectography: Recovering the Title of a 19th Century Medical Recipe Book from China

/in Aktuelles, Digitalisierung, Forschungsdaten, Handschriften/by CrossAsiaGastbeitrag von Dr. Thies Staack (Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures, University of Hamburg)

(Die deutschsprachige Version finden Sie im Stabi-Blog)

During the past few years, I have been conducting a research project on the collecting and exchange of medical recipes in 19th and early 20th century China at the Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures (CSMC) in Hamburg. Since manuscripts, both bound recipe books and individual recipes on loose leaves, played an important role in this respect, the Unschuld collection of Chinese medical manuscripts is an invaluable source for my research.

Among the close to 1,000 manuscripts from the Unschuld collection now housed at the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin Preußischer Kulturbesitz (SBB-PK), there is a small thread-bound volume with an inconspicuous outside appearance but an extraordinarily rich content of overall roughly 800 mostly medical recipes. The manuscript with the shelf mark “Slg. Unschuld 8051” was produced in 19th century Canton and attests to a vibrant exchange of medical recipes during that period. I have introduced it in some more detail elsewhere. According to the description in the catalogue of the collection, published by Paul U. Unschuld and Zheng Jinsheng in 2012, the manuscript does not have an original title, which would usually be found on the front cover or on the first page of a volume. The title provided in the catalogue – Yifang jichao 醫方集抄 or “Hand-copied collection of medical formulas” – was obviously assigned by Unschuld and Zheng based on its content.

Fig. 1: Slg. Unschuld 8051, opened at the table of contents (photo by the author).

The fact that Slg. Unschuld 8051, like many other manuscripts from the Unschuld collection, has already been digitised is of tremendous help for my research. Still, to be able to thoroughly assess the materiality of this written artefact, for example, to get a feel for its size and weight, I went to Berlin to inspect Slg. Unschuld 8051 in the SBB reading room in April 2022. The first surprise was just how small and portable the volume is (see Fig. 1). It would easily fit into a pocket or sleeve and the stains on its covers suggest that it may indeed have been carried around a lot by its previous owners.

Fig. 2: The bottom edge of Slg. Unschuld 8051 under normal interior light (photo by the author).

When I turned the manuscript in my hands, I noticed what appeared to be writing with ink on the bottom of the volume (see Fig. 2). For some of the thread-bound Unschuld manuscripts images of the top, front and bottom edge as well as the spine have been included in the digitised version. This is, unfortunately, not the case for Slg. Unschuld 8051, which was digitised already in 2014. Hence, this was the first time I got to see the bottom edge of the manuscript. Due to the darkening of the paper at the edges, it was difficult to decipher any writing, but fortunately I had brought a portable digital microscope (Dino-Lite) from Hamburg, which allows analysis with the help of light in the invisible spectrum (ultraviolet and infrared light).

Carbon ink, which was traditionally used in China, is much more clearly visible under infrared light than it is under daylight. The infrared images taken with the Dino-Lite showed clearly discernible brushstrokes (see Fig. 3). Since the area that can be photographed with the microscope’s magnification is rather small, I had to piece together several images to be able to decipher whole characters (see Fig. 4), but this was sufficient to ascertain the presence of writing.

Fig. 3: One of the infrared images taken with the help of the Dino-Lite microscope (photo by the author).

Fig. 4: Combination of four Dino-Lite infrared images, together showing the character 世, with the help of image processing software (processed image by the author).

Fig. 5: Setup of the Opus Apollo infrared reflectography (IRR) camera above Slg. Unschuld 8051 in the Berlin State Library storage (photo by the author).

In order to acquire a high-quality infrared image of the whole bottom edge, my colleagues Ivan Shevchuk, Kyle Ann Huskin and Dr. Olivier Bonnerot from the CSMC helped me capture images with a professional infrared reflectography (IRR) camera (Opus Apollo) in September 2022 (see Fig. 5). Finally, it was possible to decipher the entire inscription of five characters (see Fig. 6).

The four larger characters, which must be read choushi zhencang 酧世珍藏, from right to left, on first sight resemble a typical ownership mark of a book collector. The expression zhencang 珍藏 “treasured collection (of)” together with a personal name could constitute a statement of ownership. However, book collectors more commonly used a seal stamp and red ink to apply their ownership mark. The fifth character in slightly smaller script to the very right (shang 上) hints towards the possibility that what we have here might rather be the title of the present recipe collection. Since the table of contents at the beginning of Slg. Unschuld 8051 lists recipes in a “first volume” (shang juan 上卷) and a “second volume” (xia juan 下卷), it is clear that the recipe collection comprised overall two volumes. Comparison with the actual recipe entries shows that the present volume is indeed the first of the two, which accords well with the small character written on the bottom edge. It is also worth pointing out that traditional thread-bound books – whether handwritten or printed – often had their title inscribed on their bottom edge in addition to the cover or title page. The reason for this is a common way of storage, with books being shelved lying flat on their back with the bottom edge facing towards the front. Hence, a title placed at this position is legible while the book is stored on a shelf, similar to the title on the spine of a “Western” book.

Fig. 6: Calibrated infrared reflectography (IRR) image of the bottom edge of Slg. Unschuld 8051 (photo by Olivier Bonnerot, Kyle Ann Huskin and Ivan Shevchuk).

If choushi zhencang 酧世珍藏 is in fact the title of this recipe book, it was probably selected by the compiler of the recipes for his personal collection. At least, this title is not found in the union catalogue of Chinese medical writings. The first two characters – with 酧 being a common variant of 酬 – seem to echo the title of the popular 19th c. household encyclopaedia Choushi jinnang 酬世錦囊 “Brocade Bag of Exchange with the World”, which provided guidance on etiquette and proper social interaction. As part of the title of a recipe collection, the expression “exchange with the world” could rather refer to the way in which the compiler got hold of the recipes, many of which are indeed noted as having been received from relatives, friends or acquaintances in Canton. Hence, it might be understood as “Treasured Collection of (Recipes obtained through) Exchange with the World”.

This example showcases not only the advantages of infrared reflectography, which can allow to decipher otherwise illegible writing on manuscripts. It also points to the fact that inclusion of images of all sides of a manuscript in its digital version – in the case of thread-bound volumes also the edges and the spine – would greatly benefit research. Nevertheless, it must be stressed that even this can never entirely replace a first-hand inspection of the original written artefact in the reading room.

The data set with infrared reflectography images of Slg. Unschuld 8051 has been published as:

Olivier Bonnerot, Kyle Ann Huskin, Ivan Shevchuk and Thies Staack (2025), Infrared Reflectography Images of the Writing on the Bottom Edge of Slg. Unschuld 8051, http://doi.org/10.25592/uhhfdm.16994.

Acknowledgements:

The author thanks Dr. Cordula Gumbrecht and Dr. Andreas Janke for valuable suggestions on an earlier draft of the text.

The research behind this contribution was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy – EXC 2176 “Understanding Written Artefacts: Material, Interaction and Transmission in Manuscript Cultures”, project no. 390893796. The research was conducted within the scope of the Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures (CSMC) at the University of Hamburg.

Feature image:

Two pages from the table of contents of Slg. Unschuld 8051, showing the recipes at the end of the first and the beginning of the second volume. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – PK, Slg. Unschuld 8051, f. 23v-24r, scan pages [48]-[49] (Retrieved from http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB0000603200000048 and http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB0000603200000049)

CrossAsia Talks: Elisabeth Kaske 27.03.2025

/in Aktuelles, Veranstaltungen, Vortragsreihe "CrossAsia Talks"/by CrossAsia(See English below)

Frau Prof. Elisabeth Kaske (Universität Leipzig) wird uns am 27. März 2025 ab 18 Uhr eines ihrer aktuellen Forschungsthemen unter dem Titel “The plight of expectant officials through the lens of the daily Shenbao” im Rahmen eines neuen CrossAsia Talk vorstellen. Ihr Vortrag untersucht, wie die Shanghaier Zeitung Shenbao die prekäre Situation der “Erwartungsbeamten der späten Qing-Zeit kommentierte – ihre zunehmende Zahl durch den verkauf von Amtstiteln, ihre oft unsichere Beschäftigung und die wachsende Kritik an diesem System. Diese Analyse stützt Frau Kaske auf die digitale Auswertung der Shenbao-Archive und die damit verbundenen methodischen Herausforderungen.

State bureaucrats became an object of ridicule in many literatures of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, think of Gogol or Kafka or Li Boyuan’s Officialdom Exposed. However, they are not normally an object of compassion. This talk explores how the Shanghai daily newspaper Shenbao treated a very specific group of officials, namely the expectant officials of late Qing China.

Their numbers had become inflated by the widespread sale of official rank since the 1850s. Although they sported official titles like “magistrate” or “prefect” or “circuit intendant,” their employment situation was often precarious, with the luckier ones employed in newly established provincial bureaus. By the early 1900s, this system of parallel bureaucracies became increasingly seen as an aberration, as one commentator put it: “Foreigner are telling jokes that talent in China is defined exclusively as ‘expectant circuit intendant’. When I heard this, it makes me sweat.” (Shenbao 1907/02/22)

Wang Juan has argued that ridicule of the officialdom was a product of the tabloid press which only emerged after the failed reform movement of 1898. Before the disaster of defeat in the Sino-Japanese War gave rise to a public sphere in the late 1890s, Shenbao was (almost) the only Chinese language newspaper that commented publicly on government affairs. What was the stance of the newspaper towards the problem of expectant officials? When was it recognized as a problem? What were the solutions? When and how did a problem-solving attitude shift to ridicule and exasperation?

I have used Shenbao to gauge the changing perception of the expectant officials through almost forty years of Shenbao publishing from 1872 to 1911. Shenbao is entirely digitized. CrossAsia currently holds two versions of the Shenbao corpus. In addition, I have used the HistText corpus established by Christian Henriot and his team. However, the use of these corpuses poses methodological problems. The search “expectant official” yields a huge amount of results. Moreover, we need to distinguish journalistic comment from the memorials collected in the reprints of the Peking Gazette and from news items, which in all of these corpuses cannot be entirely mechanized. This exploratory talk from the perspective of a user of these corpuses will discuss the problems, possible solutions and tentative results.

Die Vortragssprache ist Englisch. Bei Fragen kontaktieren Sie uns unter: ostasienabt@sbb.spk-berlin.de.

Der Vortrag wird darüber hinaus via Webex gestreamt und aufgezeichnet*. Sie können am Vortrag über Ihren Browser ohne Installation einer Software teilnehmen. Klicken Sie dazu unten auf „Zum Vortrag“, folgen dem Link „Über Browser teilnehmen“ und geben Ihren Namen ein.

Alle bislang angekündigten Vorträge finden Sie hier. Die weiteren Termine kündigen wir in unserem Blog und auf unserem X-Account an.

—

Prof. Elisabeth Kaske (Leipzig University) will present one of her current research topics entitled ‘The plight of expectant officials through the lens of the daily Shenbao’ in a new CrossAsia Talk on 27 March 2025 from 6 pm. Her talk will examine how the Shanghai newspaper Shenbao commented on the precarious situation of the ‘expectant officials of the late Qing period – their increasing numbers through the sale of official titles, their often insecure employment and the growing criticism of this system. Ms Kaske bases this analysis on the digital analysis of the Shenbao archives and the methodological challenges associated with it.

State bureaucrats became an object of ridicule in many literatures of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, think of Gogol or Kafka or Li Boyuan’s Officialdom Exposed. However, they are not normally an object of compassion. This talk explores how the Shanghai daily newspaper Shenbao treated a very specific group of officials, namely the expectant officials of late Qing China.

Their numbers had become inflated by the widespread sale of official rank since the 1850s. Although they sported official titles like “magistrate” or “prefect” or “circuit intendant,” their employment situation was often precarious, with the luckier ones employed in newly established provincial bureaus. By the early 1900s, this system of parallel bureaucracies became increasingly seen as an aberration, as one commentator put it: “Foreigner are telling jokes that talent in China is defined exclusively as ‘expectant circuit intendant’. When I heard this, it makes me sweat.” (Shenbao 1907/02/22)

Wang Juan has argued that ridicule of the officialdom was a product of the tabloid press which only emerged after the failed reform movement of 1898. Before the disaster of defeat in the Sino-Japanese War gave rise to a public sphere in the late 1890s, Shenbao was (almost) the only Chinese language newspaper that commented publicly on government affairs. What was the stance of the newspaper towards the problem of expectant officials? When was it recognized as a problem? What were the solutions? When and how did a problem-solving attitude shift to ridicule and exasperation?

I have used Shenbao to gauge the changing perception of the expectant officials through almost forty years of Shenbao publishing from 1872 to 1911. Shenbao is entirely digitized. CrossAsia currently holds two versions of the Shenbao corpus. In addition, I have used the HistText corpus established by Christian Henriot and his team. However, the use of these corpuses poses methodological problems. The search “expectant official” yields a huge amount of results. Moreover, we need to distinguish journalistic comment from the memorials collected in the reprints of the Peking Gazette and from news items, which in all of these corpuses cannot be entirely mechanized. This exploratory talk from the perspective of a user of these corpuses will discuss the problems, possible solutions and tentative results.

The lecture will be held in English. If you have any questions, please contact us: ostasienabt@sbb.spk-berlin.de.

The lecture will also be streamed and recorded via Webex*. You can take part in the lecture using your browser without having to install a special software. Please click on the respective button “To the lecture” below, follow the link “join via browser” (“über Browser teilnehmen”), and enter your name.

You can find all previously announced lectures here. We will announce further dates in our blog and on X.

*Mit Ihrer Teilnahme an der Veranstaltung räumen Sie der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz und ihren nachgeordneten Einrichtungen kostenlos alle Nutzungsrechte an den Bildern/Videos ein, die während der Veranstaltung von Ihnen angefertigt wurden. Dies schließt auch die kommerzielle Nutzung ein. Diese Einverständniserklärung gilt räumlich und zeitlich unbeschränkt und für die Nutzung in allen Medien, sowohl für analoge als auch für digitale Verwendungen. Sie umfasst auch die Bildbearbeitung sowie die Verwendung der Bilder für Montagen. / By participating, you grant the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz and its subordinate institutions free of charge all rights of usage of pictures and videos taken of you during this lecture presentation. This declaration of consent is valid in terms of time and space without restrictions and for usage in all media, including analogue and digital usage. It includes image processing and the usage of photos in composite illustrations. German law will apply.

Alles neu bei der Asahi Shimbun | Everything new concerning the Asahi Shimbun

/in Aktuelles, Datenbanken/by Ursula FlacheAls neue Lizenz steht ab sofort für registrierte Nutzer:innen die japanischen Zeitung Asahi Shimbun Digital zur Verfügung. Loggen Sie sich wie üblich ein und rufen Sie das Angebot über die Datenbankseite von CrossAsia auf. Anschließend klicken Sie auf dem nächsten Bildschirm unbedingt auf「朝日新聞デジタルにアクセスする」und gelangen somit zu den Beiträgen. Nach der Recherche ist es zwingend notwendig, die Webseite rechts oben über「マイページ」und den im dortigen Pull Down Menü angebotenen Logout-Button wieder zu verlassen, da sonst unnötig Simultanzugriffe blockiert werden. Ein einfaches Schließen des Browsers beendet NICHT die Session beim Anbieter. Vielen Dank für die Kooperation!

Laut Aussage des Anbieters waren die Artikel der Papier- und der digitalen Ausgabe ursprünglich identisch. Inzwischen werden jedoch vermehrt eigenständige Artikel in der digitalen Ausgabe veröffentlicht, von denen nur 10-100 monatlich in die Datenbank Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search aufgenommen werden. Insofern sind die Inhalte der Asahi Shimbun Digital und der bereits seit längerem für CrossAsia lizenzierten Datenbank Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search nicht völlig übereinstimmend. Die Inhalte der Asahi Shimbun Digital sind jedoch nur vorübergehend verfügbar: Zeitungsartikel für 12 Monate (danach weiterhin in der Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search erhältlich), originale Online Artikel für fünf Jahre, Scans der Zeitungsseiten: 90 Tage, wohingegen die Artikel der Datenbank Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search dauerhaft archiviert werden.

Wir bedanken uns herzlich bei allen Nutzenden, die uns eine Rückmeldung gegeben haben! Ihr Feedback ist für uns wichtig und wertvoll! Vielen Dank für Ihr Engagement!

Darüber hinaus sind für die Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search weitere Inhalte lizenziert worden:

〇朝日新聞クロスサーチ「基本」

・朝日新聞1985~、AERA、週刊朝日

・朝日新聞縮刷版1945~1999(昭和戦後、平成)

・現代用語事典「知恵蔵」

・朝日新聞縮刷版1879~1945(明治・大正、昭和戦前)

・人物データベース

・歴史写真アーカイブ

・アサヒグラフ

・英文ニュースデータベース

〇Neu: 全国の地域面 地域面検索β版 >> die Jahrgänge 1991-1996 sind via Volltextsuche recherchierbar; alle anderen Jahrgänge nur via Datum (Erweiterung der Volltextsuche ist in Arbeit)

〇Neu: 戦前の外地版

___

The Japanese newspaper Asahi Shimbun Digital is now available as a new license for registered users. Log in as usual and access this resource via the CrossAsia database page. Then click on「朝日新聞デジタルにアクセスする」on the next screen to access the articles. After searching, it is absolutely necessary to leave the website via「マイページ」and use the logout button offered in the pull-down menu at the top right, as otherwise simultaneous accesses will be blocked unnecessarily. Simply closing the browser does NOT end the session with the provider. Thank you for your co-operation!

According to the provider, the articles in the paper and digital editions were originally identical. In the meantime, however, more and more independent articles are being published in the digital edition, of which only 10-100 are included in the Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search database each month. In this regard, the contents of the Asahi Shimbun Digital and the Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search database already licensed for CrossAsia are not completely identical. However, the contents of the Asahi Shimbun Digital are only available temporarily: newspaper articles for 12 months (afterwards still available in the Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search), original online articles for five years, images of the newspaper pages: 90 days, whereas the articles in the Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search database are permanently archived.

We would like to thank all users who commented on this resource! Your feedback is important and valuable to us! Thank you for your commitment!

In addition, additional content has been licensed for the Asahi Shimbun Cross-Search:

〇朝日新聞クロスサーチ「基本」

・朝日新聞1985~、AERA、週刊朝日

・朝日新聞縮刷版1945~1999(昭和戦後、平成)

・現代用語事典「知恵蔵」

・朝日新聞縮刷版1879~1945(明治・大正、昭和戦前)

・人物データベース

・歴史写真アーカイブ

・アサヒグラフ

・英文ニュースデータベース

〇New: 全国の地域面 地域面検索β版 >> the years 1991-1996 can be searched via full-text search; all other years only via date (extention of the full-text search is in progress)

〇New: 戦前の外地版

CrossAsia OA Repository: Wartungsarbeiten am 04.03.2025

/in Aktuelles, E-Publishing/by Ursula FlacheAm 04.03.2025 finden ab 10.00 Uhr Wartungsarbeiten am zentralen Datenbanksystem des CrossAsia Open Access Repository statt. Alle Anwendungen sind in der Zeit zwar grundsätzlich erreichbar; es kann aber zu kurzzeitigen Ausfällen kommen. Wir empfehlen, wenn möglich in der Zeit keine Datenbearbeitungen im Repository durchzuführen. Wir werden Sie bzgl. der Arbeiten auf dem Laufenden halten. Für die Unannehmlichkeiten bitten wir um Entschuldigung.

UPDATE: Die Wartungsarbeiten konnten zügig abgeschlossen werden. Sie können nun wieder wie gewohnt mit den Systemen arbeiten.

On March 4, 2025, the central database system of the CrossAsia Open Access Repository will undergo maintenance from 10:00 a.m. All applications will generally be accessible during this time; however, short-term outages may occur. We recommend that you do not edit any data in the repository during this time, if possible, and will keep you updated on the progress. We apologize for any inconvenience.

UPDATE: The maintenance work is finished. You can now work with the systems as usual.