CrossAsia Talks: Hermann Kreutzmann 29.01.2026

(See English below)

Wir laden herzlich zum ersten CrossAsia Talk im neuen Jahr ein. Prof. Dr. Hermann Kreutzmann (FU Berlin) wird am Donnerstag, den 29.01.2026, ab 18 Uhr zum Thema “Passages to Kashgar and Yarkand – 19th century cross-mountain connections and relations” sprechen. Der Vortrag wird die europäischen Expeditionen und geopolitischen Verflechtungen entlang der südlichen Seidenstraße im 19. Jahrhundert beleuchten. Im Mittelpunkt stehen dabei einerseits die Bemühungen von Forschern, die Handelsstädte Kashgar und Yarkand zu erreichen, andererseits die Rivalität der Kolonialmächte um Einfluss und wirtschaftliche Vorteile in Zentralasien zu jener Zeit.

The term ‘Silk Road’ first appeared in Carl Ritter’s ‘Geography of Asia’ in 1838 and was further developed and popularised by Friedrich Freiherr von Richthofen in 1877. Subsequently, geographical exploration and the search for economic advantages went hand in hand with imperial ambitions as interest increasingly focused on the Celestial Mountains and oases of the southern Silk Road. The Tianshan Mountains and Kashgar became coveted destinations for European explorers who were denied access to forbidden cities by local potentates. The prominent Berlin geographers Alexander von Humboldt and Carl Ritter motivated young scholars such as the Schlagintweit brothers to explore the roads to Kashgar and Yarkand. In addition, Pyotr Semenov participated in the Berlin nestors-led initiative to expand geographical knowledge of South and Central Asia and support its manifestation in topographical maps.

The talk focuses on efforts to reach Kashgar and Yarkand in the second half of the 19th century. The competition between Adolph Schlagintweit and Chokan Valikhanov, the role of indigenous intermediaries in gathering knowledge, and the desire to tap into the potential of valuable local commodities have shaped our perception of the southern Silk Roads. Kashgar and Yarkand were hubs for trade between Afghanistan, Semirechia, Kashmir, and British India. The Xinjiang Triangle represents a less significant case within the colonial opium regime, but with significant local impact on consumers, trade and profit. The exchange corridors were characterised by long-distance routes connecting rival empires, represented by Chinese administrative officials, British and Russian consuls, with Kashgar and Yarkand. The archival material presented, spanning a century from the 1850s, was recorded by European representatives on site and provides insights into the external perception of these oases on the Silk Road. Comparisons of favourable routes led to dreams of infrastructure projects to cross the Karakorum Mountains and Kunlun Shan, which were realised in the second half of the 20th century.

Die Vortragssprache ist Englisch. Bei Fragen kontaktieren Sie uns unter: ostasienabt@sbb.spk-berlin.de.

Der Vortrag wird via Webex gestreamt und aufgezeichnet*. Sie können am Vortrag über Ihren Browser ohne Installation einer Software teilnehmen. Klicken Sie dazu unten auf „Zum Vortrag“, folgen dem Link „Über Browser teilnehmen“ und geben Ihren Namen ein.

Alle bislang angekündigten Vorträge finden Sie hier. Die weiteren Termine kündigen wir in unserem Blog und auf unserem X-Account, Mastodon und BlueSky an.

—

We cordially invite you to the first CrossAsia Talk of the new year. Prof. Dr. Hermann Kreutzmann (Freie Universität Berlin) will speak on Thursday, January 29, 2026, at 6 p.m. on the topic “Passages to Kashgar and Yarkand – 19th-Century Cross-Mountain Connections and Relations.”

The lecture will explore European expeditions and geopolitical entanglements along the southern Silk Road in the 19th century. It will focus on the efforts of researchers to reach the trading cities of Kashgar and Yarkand, as well as on the rivalry among colonial powers for influence and economic advantage in Central Asia at that time.

The term ‘Silk Road’ first appeared in Carl Ritter’s ‘Geography of Asia’ in 1838 and was further developed and popularised by Friedrich Freiherr von Richthofen in 1877. Subsequently, geographical exploration and the search for economic advantages went hand in hand with imperial ambitions as interest increasingly focused on the Celestial Mountains and oases of the southern Silk Road. The Tianshan Mountains and Kashgar became coveted destinations for European explorers who were denied access to forbidden cities by local potentates. The prominent Berlin geographers Alexander von Humboldt and Carl Ritter motivated young scholars such as the Schlagintweit brothers to explore the roads to Kashgar and Yarkand. In addition, Pyotr Semenov participated in the Berlin nestors-led initiative to expand geographical knowledge of South and Central Asia and support its manifestation in topographical maps.

The talk focuses on efforts to reach Kashgar and Yarkand in the second half of the 19th century. The competition between Adolph Schlagintweit and Chokan Valikhanov, the role of indigenous intermediaries in gathering knowledge, and the desire to tap into the potential of valuable local commodities have shaped our perception of the southern Silk Roads. Kashgar and Yarkand were hubs for trade between Afghanistan, Semirechia, Kashmir, and British India. The Xinjiang Triangle represents a less significant case within the colonial opium regime, but with significant local impact on consumers, trade and profit. The exchange corridors were characterised by long-distance routes connecting rival empires, represented by Chinese administrative officials, British and Russian consuls, with Kashgar and Yarkand. The archival material presented, spanning a century from the 1850s, was recorded by European representatives on site and provides insights into the external perception of these oases on the Silk Road. Comparisons of favourable routes led to dreams of infrastructure projects to cross the Karakorum Mountains and Kunlun Shan, which were realised in the second half of the 20th century.

The lecture will be held in English. If you have any questions, please contact us: ostasienabt@sbb.spk-berlin.de.

The lecture will be streamed and recorded via Webex*. You can take part in the lecture using your browser without having to install a special software. Please click on the respective button “To the lecture” below, follow the link “join via browser” (“über Browser teilnehmen”), and enter your name.

You can find all previously announced lectures here. We will announce further dates in our blog and on X, Mastodon and BlueSky.

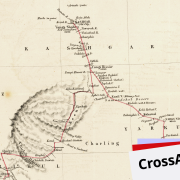

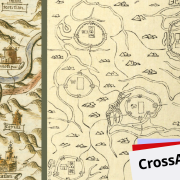

Caption for Mirza’s exploration map:

The ‘Map of the route from Badakhshan across the Pamir-Steppe to Kashgar with the southern branch of the Upper Oxus from the survey made by the Mirza in 1868-69’ accompanied a paper read at the Royal Geographical Society on April 24, 1871 by Thomas Montgomerie and was published in the society’s journal in the same year. It shows Mirza Shuja’s explorations along his route from Badakhshan to Shahidulla via Kashgar.

Source: Thomas George Montgomerie 1871: Report of ‘The Mirza’s’ Exploration from Caubul to Kashgar’ in Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London 41, page 132 opposite.

Source: Reproduced in Pamirian Crossroads (2015: 213); Courtesy Pamir Archive Collection