Highlighting a ‘Forgotten’ Perspective on the First World War: German POWs in Japan and the Bandō-Sammlung

Gastbeitrag von Prof. Sarah Panzer

The staggering quantity of literature on the First World War can give rise to the mistaken impression that scholars have already said all that there is to say on the topic, especially in the wake of the many fine publications which emerged out of the centenary commemorations of the conflict. Growing recent interest in the conflict’s global dimensions, as well as the diverse experiences of captivity and internment faced by military prisoners and civilians alike, however, have illuminated new directions for scholars to pursue. Even within this literature, the East Asian front of the First World War has been largely relegated to the status of a historical footnote, a function both of its geographic distance and its brevity, at least militarily.

On 23 August 1914, Japan declared war on Imperial Germany, using its alliance with Great Britain as a convenient pretext in claiming Germany’s colonial possessions in Asia for its own. By mid-October the Japanese Navy successfully occupied German Micronesia and on 7 November the German garrison at Tsingtao (Qingdao) surrendered to the 18th Infantry Division of the Japanese Imperial Army, supported by a symbolic contingent of British troops. The nearly 4,700 German and Austrian servicemen captured at Tsingtao were subsequently transported to the Japanese mainland, where they were housed in a series of temporary camps throughout central Japan. Once it became clear that the war would not be ending as quickly as initially predicted, these camps were replaced by larger, more comfortable facilities intended to mitigate the prisoners’ boredom and loneliness.

Repatriation of the POWs only began in 1919, with the final prisoners returning to Germany (excepting those who chose to remain in Asia) in 1920. Over the course of their five-year captivity, these men produced a significant archival record of their lives in Japan, including camp newspapers, printed objects such as concert programs and postcards, personal diaries and memoirs, and dozens of photographs. The Bandō-Sammlung, held since late 2021 in the Ostasienabteilung of the SBB-PK, sheds invaluable light on a dimension of that conflict which has been so far largely overlooked by researchers outside of Japan.

The Best Camp in the World

Camp Bandō was one of the ‘second generation’ camps opened during the war; it opened in early April 1917 and was officially closed three years later, on 1 April 1920. Located on the island of Shikoku and built to accommodate the prisoners previously held in the camps in Matsuyama, Marugame, and Tokushima, Bandō quickly acquired a reputation as a model camp because of its many well-resourced facilities and opportunities for cultural and social diversion. The camp included living quarters, administrative buildings, kitchens, and baths, as well as two small lakes (one of which was used by the prisoners for boating) and a small ‘commercial district’ with some eighty shops, specializing in everything from bookbinding and photography to furniture construction and musical instrument repair. (Fig. 1) Just outside the camp the prisoners also had access to a large sports complex, which boasted a soccer field, a Turnhalle, and eight tennis courts.

Fig. 2: A group of students waits in line to enter the exhibition of “visual arts and handicrafts” organized by the residents of Bandō POW camp. The exhibition was hosted by the nearby Ryōzenji temple, hence the statue in the center of the image. A no less imposing bearded German soldier is visible on the lefthand side of the photo. SBB-PK. Bandō-Sammlung H 57-07.

Even at the time, prisoners referred to Bandō as the “best camp in the world,” and both the camp and its commander—Lieutenant Colonel Toyohisa Matsue—have become synonymous in contemporary popular memory in Japan with a humane and tolerant approach to internment, which facilitated not only a (relatively) pleasant experience for the prisoners themselves, but also a mutually beneficial circuit of cultural and intellectual exchange between the German prisoners and their Japanese neighbors. One striking example was the exhibition of “visual arts and handicrafts” organized by Bandō’s residents in March 1918. Visitors could peruse the works on display—which included everything from oil paintings to technical models to taxidermied local birds—at their leisure or receive a guided tour by a prisoner-translator, visit one of the concession stands and sample ‘authentic’ German baked goods, try their luck at one of the carnival games operated by the prisoners outside, or simply relax and listen to music performed by one of the camp’s multiple ensembles. (Fig. 2) With a reported total attendance of just over 50,000 visitors over twelve days, Bandō’s camp newspaper Die Baracke concluded that the exhibition had been a triumph of cultural diplomacy:

“Thousands of inhabitants of the country which holds us captive have admired the works of German POWs with their own eyes, and hundreds of thousands have heard about them through word of mouth and newspapers. To those who had been repeatedly exposed to the image of the German Barbarian since the beginning of the war, we were able to show them with our exhibit ‘Hie gut Deutschland alleweg!’—Thus, even with our modest resources, we were able to render a service to the Fatherland.”

(Die Baracke I, no. 25 [17 March 1918], 42. SBB-PK. Bandō-Sammlung A 2-1)

This quotation is a useful reminder that, their official status as POWs notwithstanding, the residents of Bandō saw themselves as participants in the ongoing global war. The activities and groups with which they occupied themselves were never simply about staying busy; they were also meant to project an image of German resilience, strength, and cultural superiority meant to function as ‘counter-programming’ to British and French propaganda.

Fighting Vicariously

The POWs held in Japan were avid consumers of news about the war’s progress, militarily and politically. Far from being isolated from the events back in Europe, prisoners were kept up-to-date through regular telegram transmissions—in the case of Bandō, these transmissions were recorded daily and made available to the camp’s residents through a subscription-based bulletin—from New York, London, Paris, and Moscow. German-language media was less consistently available, but newspapers, books and other printed materials shipped from Europe provided prisoners with an invaluable sense of connection to the German war effort. This ongoing interest in the war was, in one sense, eminently practical—although rumors of prisoner swaps or early parole persisted, most recognized that they were ‘stuck’ in Japan until the war ended—but it also speaks to the powerful sense of national unity and purpose which emerged in German-speaking Europe during the First World War.

Die Baracke featured monthly articles summarizing the major battles, personalities, and strategic developments on the war’s various fronts, as well as significant political events like the October Revolution in Russia. Likewise, President Woodrow Wilson’s public comments and speeches denouncing German autocracy and claiming that the US was fighting to secure a just and lasting peace for the peoples of the world, was met with scathing commentary in the pages of Die Baracke, with one article sarcastically responding, point-by-point, to Wilson’s rhetoric:

“‘America refuses to impose its will by exploiting the weakness and internal unrest of other countries.’

Fig. 3: Illustration of German trenches on the Western Front. The almost bucolic scene betrays the illustrator’s lack of familiarity with the realities of trench warfare. Drei Märchen von E. Behr. SBB-PK. Bandō-Sammlung B 06.

But you should not have said that Herr Professor… Mr. President! Or has your noble life’s work, the study and destruction of brutal German militarism, so completely occupied you that you have never heard of the Spanish-American War – it was in 1898? Your high-minded country has its own delicate American militarism, which was quite involved at the time ‘exploiting the weakness of other countries,’ to thank for the not quite so independent, rich island of Cuba and the likewise not entirely poor, not entirely independent Philippines.”

(Die Baracke I, no. 22 [24 February 1918], 13-14. SBB-PK. Bandō-Sammlung A 2-2)

On one level, these articles reflect the appetite for news about the war, in all its various dimensions, among the POWs in Japan; other articles published in Die Baracke, as well as public lectures in the camp, commented on modern military technology and tactics, specific battles, and the mobilization of the home front. Indeed, one of the more interesting artifacts of the Bandō-Sammlung is the lavishly illustrated book of modern German fairy tales published by the camp printing press in 1918; the first of the three stories takes place largely in the trenches of the Western Front, already an icon of contemporary cultural memory which neither the story’s author nor its illustrator had ever actually seen for themselves. (Fig. 3)

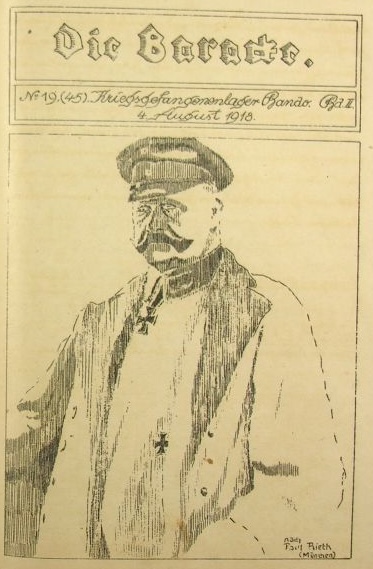

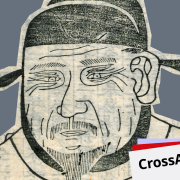

More meaningfully, however, they also demonstrate the intense emotional investment of the POWs with the German state, the German war effort, and with German war nationalism more generally. Kaiser Wilhelm II’s birthday was celebrated in the camp with lavish festivities, and tributes to the Prussian royal dynasty, Bismarck, and Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg became a regular feature in Die Baracke. (Fig. 4)

Fig. 4: A special cover of Die Baracke celebrating the hero of Tannenberg Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg. By 1918 a veritable cult of personality had coalesced around Hindenburg in Germany, and apparently in Bandō as well. Die Baracke II, no. 19 (4 August 1918), 489. SBB-PK. Bandō-Sammlung A 2-2.

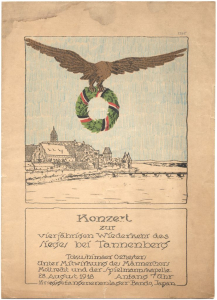

Notable battles from earlier in the war, such as the Battle of Tannenberg, were commemorated with special concerts. (Fig. 5) Nor were the residents of Bandō content to be mere observers, their circumstances notwithstanding; they (re)mobilized themselves as active participants in the war effort through fundraisers on behalf of their fellow German POWs in Siberia. It is not entirely surprising that the war would have been on the minds of these men; what is noteworthy, however, are the patterns revealed by their consumption of news and propaganda as an integral element of their performance as good and loyal Germans.

Fig. 5: Program for a concert by the Tokushimaer Orchestra in commemoration of the fifth anniversary of the Battle of Tannenberg. SBB-PK. Bandō-Sammlung E 3-17.

The German and Austrian POWs held in Japan during the First World War were determined to not be forgotten by their political leaders and fellow countrymen. Accordingly, they documented their lives in Japan, their thoughts on the war, and their feelings towards German culture and national identity in a variety of sources. This research was conducted as part of a broader project examining the POW camps in Japan as sites of cultural engagement and exchange, but also transformation as the prisoners were forced to reconcile their previous relationship to the German nation with the reality of defeat and decolonization.

Frau Prof. Sarah Panzer, Missouri State University, war im Rahmen des Stipendienprogramms der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz im Jahr 2025 als Stipendiatin an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Forschungsprojekt: „German-Austrian Prisoners of War (POWs) in Japan during the First World War“

Vortrag im Rahmen von CrossAsia Talks am 04.09.2025

Dieser Beitrag erschien zuerst im SBB-Blog.

Tang Sanjiao

Tang Sanjiao

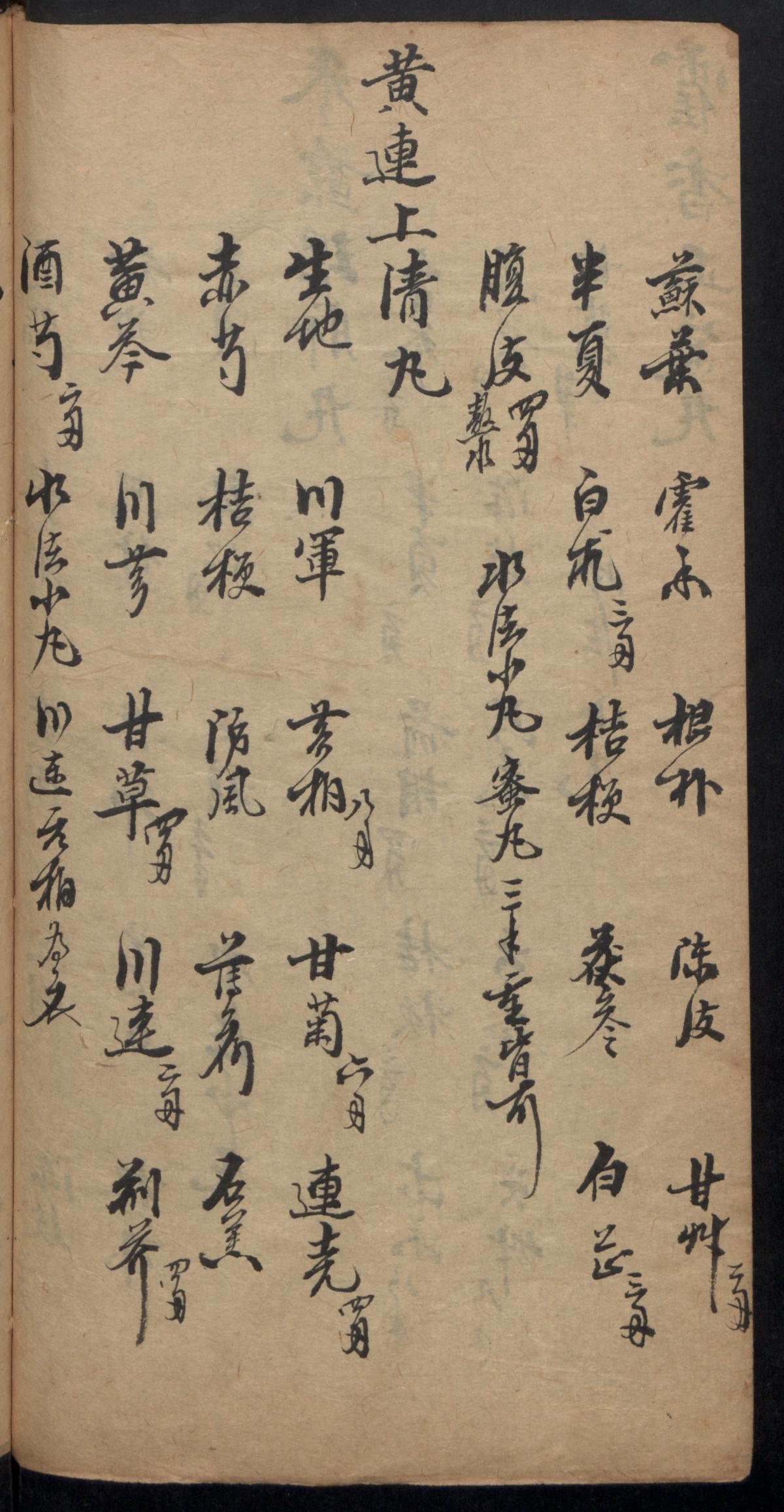

![Image 2. “On the Map of the Barbarians in the Four Directions“. - In: Zhang Tianfu 張天復 (d. 1578), first pages of “Si Yi tushuo” 四夷圖說, in Guang huang yu kao 廣皇輿考 (Analysis of All Imperial Territories, 16th century), juan 18, p. 5a–b. Retrieved from https://id.lib.harvard.edu/alma/990077608260203941/catalog [18.01.2024] (n.p.: Zhang Rumao 張汝懋, Ming Tianqi bing yin 明天啓丙寅 [1626]), original held and scanned by Harvard University. - The book can also be found in the SBB in Siku jinhuishu congkan 四庫禁燬書叢刊 (Beijing: Beijing chubanshe, 2000), “Shibu” 史部, vol. 17, p. 352 (2000–2005), SBB PK: 5 B 33312 17](https://blog.sbb.berlin/wp-content/uploads/Chin.Buecher-Henschel-Bild-2-Vers-2.jpg)

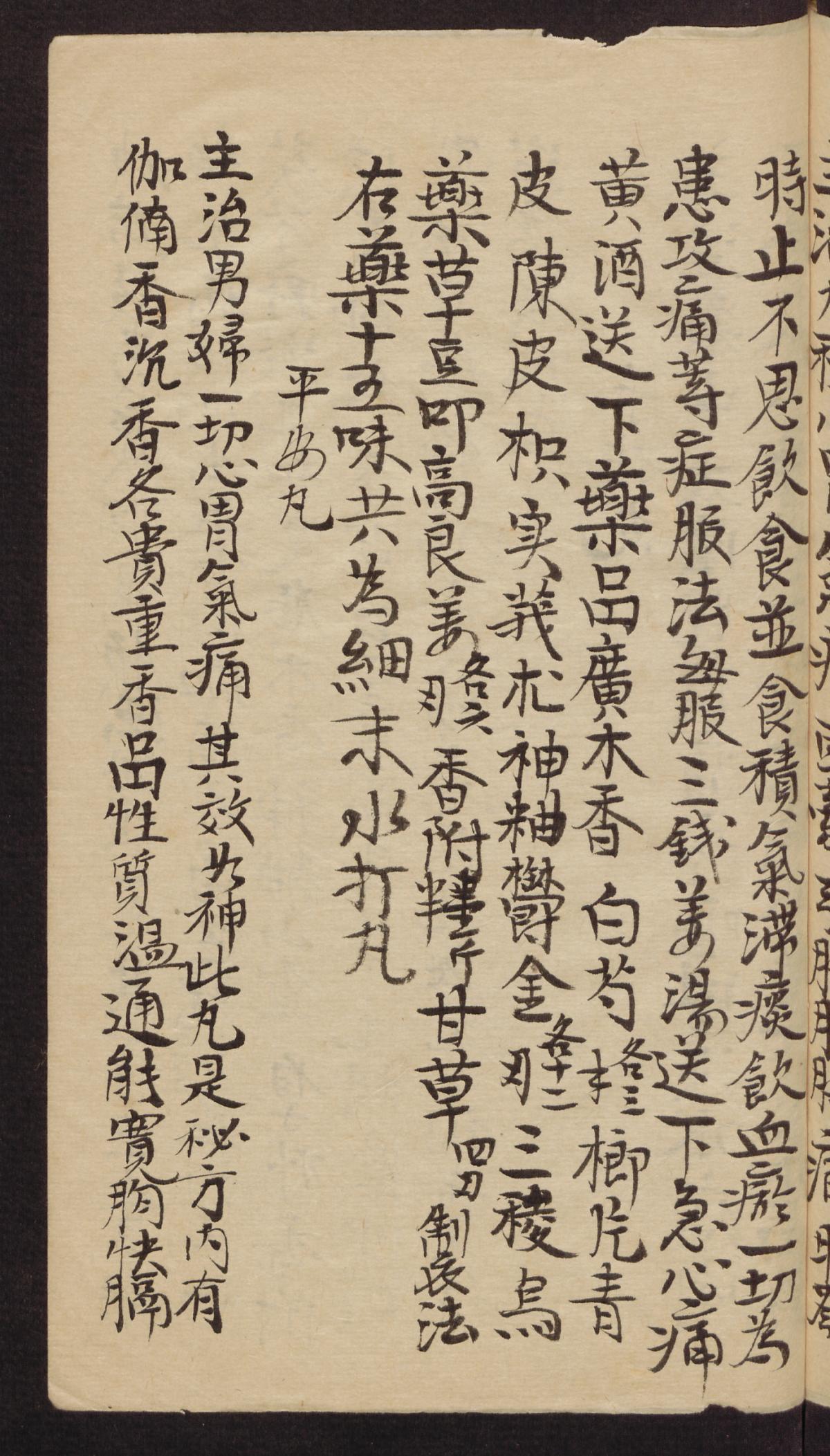

![Image 3: “Complete Report of Studying History, late 16th or early 17th century”. - In: Yu Shenxing 于愼行 (1545–1608), Du shi man lu 讀史漫錄, juan 13, p. 5b–7a. - Retrieved from https://id.lib.harvard.edu/alma/990077598390203941/catalog [18.01.2024] (n.p.: Yu Wei 于緯, Ming Wanli jia yi n 明萬曆甲寅 [1614]), original held and scanned by Harvard University. - A reprint of a different edition can be found in SBB in Siku quanshu cunmu congshu 四庫全書存目叢書 (Jinan: Qi Lu shushe, 1996), “Shibu” 史部, “Shiping lei” 史評類, vol. 285, p. 654 (juan 13, p. 4a–5b), SBB PK: 5 B 33301 285](https://blog.sbb.berlin/wp-content/uploads/Chin.Buecher-Henschel-Bild-3.jpg)