„Tidying Up Texts“ – CrossAsia has published its first n-gram packages for download

Perhaps you have seen Ursus Wehrli’s book “Tidying Up Art” where he takes pieces of art, separates the various shapes and colours and sorts them into neat heaps (see for example Keith Haring’s painting “Untitled” from 1986 here). N-grams aim to achieve somewhat similar: A text is segmented into component parts and identical parts are put together and counted. Arguably, this is an even more economical way of “tidying up” than that used by Mr Wehrli. The original structure and meaning of the text is disassembled and the text is viewed from a strictly statistical angle on the basis of these parts of the text. What we consider the “parts” of a text is not fixed. For example, parts of a Latin script text can be individual letters, or words identified by spacing, or two or more consecutive words or letters.

“Tidying up” texts in East Asian scripts

The safest “parts” that can be identified in East Asian scripts are the individual characters (either Chinese characters or Japanese and Korean syllables). Let’s take the first two phrases of the Daode jing to show how straightforward the basic concept of n-grams is:

道可道,非常道。名可名,非常名。無名天地之始, 有名萬物之母。

With unigrams (also called 1-grams), every individual character counts as a unit (we skip the punctuation which normally doesn’t exist in historical versions of this text). For this short passage, a list of unigrams and their frequencies looks like this:

名, 5

道, 3

可, 2

非, 2

常, 2

之, 2

無, 1

天, 1

地, 1

始, 1

有, 1

萬, 1

物, 1

母, 1

With bigrams (or 2-grams), two consecutive characters count as a unit. Consequently, the units overlap each other by one character (道可, 可道,道非 and so on). The result is the following:

非常, 2

道可, 1

可道, 1

道非, 1

常道, 1

道名, 1

名可, 1

可名, 1

名非, 1

常名, 1

名無, 1

無名, 1

名天, 1

天地, 1

地之, 1

之始, 1

始有, 1

有名, 1

名萬, 1

萬物, 1

物之, 1

之母, 1

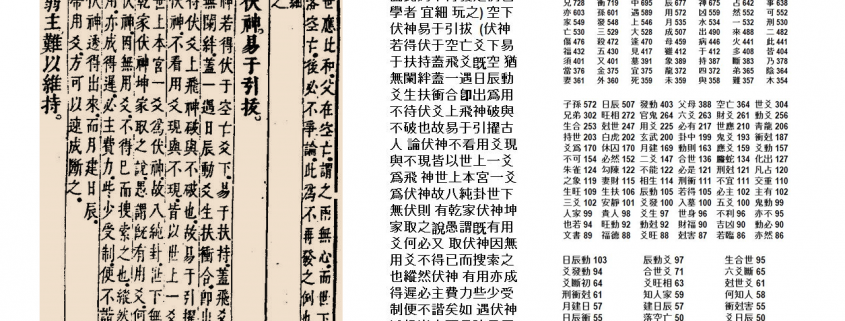

In the case of trigrams (or 3-grams) the lists get even longer and – when taking this short paragraph as the basis – each of the trigrams (道可道, 可道非, 道非常) would appear just once. Two things become immediately clear: n-grams only make sense for longer texts and n-gram lists grow quickly in size. The corpus of the Xuxiu Siku quanshu 續修四庫全書 with 5,446 titles produces 27,387 unigrams and 13,216,542 bigrams; even a title like Buwu quanshu 卜筮全書 (which is used in the header) has 3,382 unigrams, 64,438 bigrams and 125,010 trigrams.

Long lists – and then?

Only n-gram lists of complete books or large text corpora are capable of building the basis for analyses interpreting the contents at large: do specific n-grams often appear together? What is noticeable when comparing n-gram lists of different books or corpora with each other? When putting these n-gram lists back into the context of the bibliographical information about the specific books, are there any discernable shifts over time, in the oeuvre of an author or in a certain genre? What appears where more or less often or what n-grams appear or not appear together?

Two well-established sources of n-grams are the Google-Ngram Viewer or the HathiTrust Bookworm. Both are known for displaying shifts in popularity of certain terms over time. But n-grams – maybe cleaned and sharpened using additional analytical means – can be the raw material for even more advanced explorations and hypotheses. Many of the things that n-grams can detect are also discernible via “close reading” – of course! But n-grams are ruthlessly neutral, approaching texts with purely statistical means unaffected by reading habits and preconceptions of the field. And they have one more big advantage: the original (license protected) fulltext disappears behind a statistical list of its parts and thus does not violate the license agreements CrossAsia has signed with its commercial partners.

Step by step into the future

The header image on top of this blog post shows an original print face of the Buwu quanshu 卜筮全書, the corresponding (searchable) fulltext and lists of uni-, bi- and trigrams for the whole text. Without further information, the lists themselves are of limited use. Only by comparing them with other lists and analyzing them using digital tools and routines comes their full potential to the fore. The number of our users that can do their own analyses on the basis of n-grams will surely grow within the next years, especially since many curricula in the humanities have started to include analytical methods using digital humanity tools and “distant reading”. But we at CrossAsia are also working on services – in addition to providing the n-gram lists themselves (CrossAsia N-gram Service) – that allow users to explore, analyze and visualize these n-grams. Our aim is to give a better overview and access to the growing number of texts hosted in our CrossAsia ITR (Integrated Text Repositorium).

First accomplishments

A first tool developed by CrossAsia aiming to help users find relevant materials is the CrossAsia Fulltext Search that went online April 2018 in a “guided” and an “explorative” version. The search currently covers about 130,000 titles and over 15.4 million book pages. The Fulltext Search works on the basis of a word search in combination with the metadata of the titles. This is a good start but we presume that in the long run it will not be able to fulfill the requirement to guide users to resources relevant to their research question – at least not alone. One obstacle is the divergence of metadata of the titles so that no clean filter terms to drill down search results can be offered. Another obstacle is the sheer number of returned hits which make it impossible to gain a clear overview.

N-grams and the corresponding tools can help find similarities between texts or identify the topics of a text, among other things. Thus, they provide ways to look at texts not only from the angle of their bibliographic description but make the texts “talk about themselves”. N-grams, topic modeling (i.e. an algorithm-based identification of the topics of a text), named-entity recognition (i.e. the automatic detection and mark-up of personal or geographic names etc.) are forms of such self-descriptions of a text. We at CrossAsia are currently experimenting with different forms of access, visualization and analysis of the contents stored in the CrossAsia ITR that will supplement the Fulltext Search in the near future.

CrossAsia N-Gram Service

The first three sets of n-grams (uni-, bi- and trigrams) of texts stored in the CrossAsia ITR have been uploaded and are now available to all users, CrossAsia and beyond (CrossAsia N-gramn Service). The three sets are 1. the Xuxiu Siku Quanshu續修四庫全書corpus of 5,400+ historical Chinese titles; 2. the Daoist text compendium Daozang jiyao 道藏辑要 with about 300 titles compiled in 1906; and 3. a collection of over 10,000 local gazetteer titles covering the period from the Song dynasty to Republican China and some older geographical texts.

The n-grams of these sets are generated on the book level, with the name of a book’s n-gram file matching the ID given in the metadata table of the specific set, which is also available for download. A few caveats for this first version of n-gram sets: we did not check the sets for duplicates (so the local gazetteer set might contain the same text more than once); we did not do any kind of character normalization (which would have counted the variants 回, 囬, 廻, 囘 as the same character); and we removed any kind of brackets such as【 and 】etc. that in some cases marked entries or sub-chapters in the texts. So, as with all algorithms, the ruthless neutrality of n-grams claimed above in fact depends on sensible preprocessing decisions, and no decision can be equally well-suited for all possible research questions.

We are curious!

Are these n-gram sets helpful for your research? What can we improve? Do you have suggestions for further computer based information about the texts we should offer in our service? We look forward to hearing your feedback about this new CrossAsia service!

Diskutieren Sie hierzu im CrossAsia Forum