(Un)official Korean Sources on late Koryŏ in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin’s East Asian Collection

Gastbeitrag von Lukáš Kubík

Dieser Beitrag erschien zuerst auf dem Blog der Staatsbibliothek.

During the mid‑fourteenth century, East Asia experienced a period of profound changes, labelled by researchers as the Great Chinggisid Crisis, corresponding to Europe’s Crisis of the late Middle Ages. This era was marked by significant climate changes, leading to several disasters, including natural calamities, famines, and plagues. These events set the stage for major political upheavals. The once mighty Mongol Empire (1206–1368) began to decline, paving the way for the rise of the Red Turbans, a new power in China that led to the founding of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). At the same time, Japan faced its own turmoil during the Northern and Southern Courts period, characterized by intense rivalry between the two imperial courts. In Korea, these turbulent times led to a significant shift in power as well. The Korean state of Koryŏ (918–1392) gave way to the Chosŏn dynasty (1392–1910) by the end of the fourteenth century. This transition was part of a broader pattern of dramatic changes that reshaped the entire region of East Asia.

Today’s historians of East Asia have access to a rich collection of written sources spanning an impressive geographic and cultural range. These materials, originating from China, Japan, Central Asia, Arabic-speaking countries and Europe, provide a multifaceted view of the region’s historical landscape. The main written Korean historical sources for this period are the Koryŏsa 高麗史 (History of Koryŏ) and Koryŏsa Chŏryŏ 高麗史節要 (The Essential History of Koryŏ), both in the category of dynastic histories and annalistic works. These are “official” historical documents written by court historians, which offer valuable information about historical periods. The political agenda and ideologies of the ruling dynasty influenced the compilation of official histories and veritable records. Most of the sources are retrospective. That means in the case of Korea, the Chosŏn dynasty historians composed the History of Koryŏ; in the case of the Yuan dynasty, it was the Ming dynasty historians that wrote the History of Yuan. Different historiographical biases have particular traditions in Chinese historiography (and in historiography in general per se); for instance, the emphasis on moral judgment and categorising rulers into “good” or “bad” based on Confucian principles can lead to a somewhat simplistic or one-dimensional portrayal of historical figures. Historians working on these works also might have faced censorship leading them to exclude sensitive or controversial information. Additionally, self-censorship might have prompted historians to avoid topics that could jeopardise their positions or provoke the ruling regime. Official histories are typically compiled after the end of a dynasty or reign of the ruler, meaning historians may have been influenced by knowledge of later events. This can lead to a tendency to view past events through the lens of present circumstances, possibly distorting the interpretation of historical events. Chinese and Korean official histories also exhibit a degree of ethnocentrism, portraying China as the centre of the world and other cultures or nations as peripheral or subordinate. This perspective can result in a biased understanding of regional or global historical dynamics.

Alongside the official histories, an array of unofficial written sources offers a broader perspective on historical events. These include, for example, educational materials developed for private academies, known as Sŏwŏn 書院 in Korean, which summarize Korean history by drawing from a variety of earlier texts. Additionally, collections of personal writings and records from scholars, officials, and literati, known as Munjip 文集, provide invaluable insights into individual viewpoints and experiences often missing in official narratives.

One significant repository for such materials in Europe has been the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz. This collection, however, has been dispersed, with parts of it now residing in both Berlin and Kraków. Despite this geographical split, a collaborative effort known as the Berlin-Kraków Project has made these resources more accessible. Through this initiative, the East Asian sources housed in Poland are digitized, allowing scholars and the general public to explore these documents online.

In this blog post, I’ll explore several unofficial historical Korean sources in the East Asian collection of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. These sources shed light on the 14th century and beyond, offering rich alternatives to the more conventional dynastic records.

Cover of Tongguk t’ongkam chekang (The Basic Framework of the Comprehensive Mirror of the Eastern Kingdom). – SBB-PK:. Libri cor. 23, image 1

One of these alternative sources for Korean history is the Tongguk t’ongkam chekang 東國通鑑提綱 (The Basic Framework of the Comprehensive Mirror of the Eastern Kingdom), compiled by scholar Hong Yŏha (洪汝河, 1620–1674) in the 17th century. This work served as an instructional resource for private academies. It encompasses a historiography of Korean history, tracing from the Ancient Chosŏn to the Unified Silla (668–935) period. Notably, this text represents one of the earliest instances of exploring questions of legitimacy within ancient Korean history. It is generally known that it was published in 1786 with an introduction by An Chŏngbok (安鼎福 1712–1791). The book is printed using wooden type and consists of 13 volumes (卷) across 7 books (冊). It has been preserved and digitized at major South Korean archives, including the Kyujanggak and Jangseogak. Copies are also available at the Harvard-Yenching Library, Princeton, and Berkeley. In Europe, it is only found at the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Therefore, it is quite a rare document, making the digitized version a valuable resource for researchers interested in accessing the original text.

Tongguk t’ongkam chekang: Introduction by An Chŏngbok. – SBB-PK:. Libri cor. 23, image 9

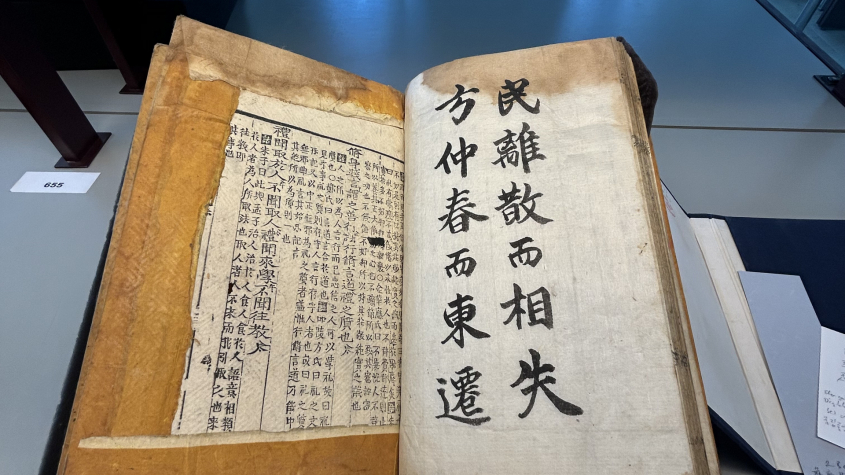

Another example is the Yŏsachekang 麗史提綱 (Annotated Outline of Koryŏ History), compiled by Yu Kye (兪棨, 1607–1664) in the 17th century.

Cover of the Yŏsachekang (Annotated Outline of Koryŏ History). – SBB-PK: Libri cor. 18, image 1

This work comprehensively covers the history of Koryŏ, spanning from the reign of King T’aejo of Koryŏ (太祖, 918–943) to the reign of King Ch’ang (昌王, r. 1388–1389). This manuscript represents a significant development in Chosŏn-period historiography influenced by Confucianism. The first edition was compiled in 1667, three years after Yu Kye’s death. In 1749, King Yŏngjo took issue with the record of King Kongyang (恭讓王, r. 389–1392) and had it reprinted; there are, therefore, two versions. Looking at the differences from the first edition, the expression ‘夷狄禽獸’ in the preface written by Song Si-yŏl 宋時烈 (1607–1689), which King Yŏngjo pointed out, has been changed to ‘倫綱弗正’, and other parts of the records of King Kongyang were deleted. The book is printed using wooden type and consists of 23 volumes (卷) across 23 books (冊). It has been preserved and digitized at major South Korean archives, including Kyujanggak and Jangseogak, but also in North Korea at the Grand People’s Study House (인민대학습당). Copies are available at Harvard’s Yenching Library, Princeton, Library of Congress, and Indiana University. In Europe, it is only at the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin.

Preface 序 to the Yŏsachekang (Annotated Outline of Koryŏ History). – SBB-PK: Libri cor. 18, image 4

Another indispensable alternative source for exploring Korean history is the Munjip (文集), a compilation that gathers essays, poetry, and other writings by one or several individuals. In Korea, the scope of Munjip is broad, encompassing records, collected works, compilations, posthumous works, daily records, complete works, collected letters, comprehensive collections, and factual records. These collections serve not only to preserve individual legacies for posterity, but also as a rich repository of diverse personal experiences.

The material value of Munjip for historical research is profound. Each collection offers a unique lens through which to view the past, reflecting their authors’ personal insights, cultural contexts, and intellectual climates. This personal dimension allows historians and scholars to access a range of narratives that might otherwise be lost in more formal historical accounts.

Front cover of the Collected Works of P’oŭn . – SBB-PK: Libri cor. 27, image 1

One noteworthy example of Munjip in the holdings of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin is the P’oŭnjip 圃隱集 (Collected Works of P’oŭn). P’oŭn was the pen name of Chŏng Mong‑ju 鄭夢周 (1337–1392), a distinguished Confucian scholar and politician from the late Koryŏ dynasty. P’oŭn’s life and career were profoundly intertwined with the turbulent political shifts of his time, culminating in his assassination by Yi Pang-wŏn, the third king of the Chosŏn dynasty. This act was motivated by P’oŭn’s steadfast loyalty to the Koryŏ dynasty and his opposition to Yi Sŏng-gye, Yi Pang-wŏn’s father and the founder of the Chosŏn dynasty. Chŏng Mong‑ju held several key positions within the Koryŏ government, including Minister of Civil Appointments, Director of the Royal Academy, and Supervisor of the Office of Personnel. He was a significant figure during a time when factions within the Koryŏ court were deeply divided between the ones supporting the declining Yuan dynasty and supporters of the rising Ming dynasty. Chŏng emerged as a staunch advocate for pro-Ming policies among progressive scholars and demonstrated considerable diplomatic skills, serving as an envoy to both Ming China and Japan.

Portrait of Chŏng Mong‑ju in the Collected works of P’oŭn. – SBB-PK: Libri cor. 27, image 4

The P’oŭnjip was first published in 1439. This collection represents a significant literary work that has accumulated various editions and supplements over the centuries. There are several editions of P’oŭnjip located in archives:

1. Old Edition (舊本), published in 1439: Initially published by his sons Jong Sŏng 宗誠 and Jong Bon 宗本. It was mentioned that Chŏng Mong‑ju’s works had been collected since 1409, indicating thirty years until the first edition’s publication.

2. Shingye Edition (新溪本), published in 1533: Updated by his descendant Se-shin 世臣 while serving as a county magistrate in Shingye, adding a chronological record to the original edition.

3. Kaesŏng Old Print Edition (開城舊刻本): Early in the reign of King Sŏnjo (宣祖 r. 1567–1608), this edition added three new poems to the original content. The exact year of publication remains unknown.

4. Scholar’s Library Edition (校書館本): Published in metal type during the early to mid-reign of King Sŏnjo.

5. Yŏngchŏn First Print Edition (永川初刻本), published in 1584: Compiled and revised under the commission of Yu Sŏng‑yong (柳成龍, 1542–1607). This edition was recompiled in 1607 by Yŏngchŏn magistrate Hwang Yŏ‑il (黃汝一, 1556–1622) and scholars from the Imgo Sŏwŏn 臨皐書院 after the original plates were destroyed during the Japanese invasions (Imjin War, 1592–1598).

6. Bonghwa Print Edition (奉化刻本), published in 1659, was carved by a descendant, Yu Sŏng (維城, ??) in Bonghwa. It has added sections on chronological discrepancies and ritual texts.

7. Yŏngchŏn Reprint Edition (永川再刻本), published in 1677: Reprinted in Yŏngchŏn with added corrections from the Bonghwa edition and extended records from various families, expanding the content from 4 to 9 volumes.

8. Kaesŏng Reprint Edition (開城再刻本), published in 1719: This edition was further expanded by a descendant, Ch‘an Hwi (纘輝, ??), who added three additional volumes of records to the four volumes of the Bonghwa edition. This extended content was eventually published in Kaesŏng in 1769.

9. Kaesŏng New Edition (開城新本), published in 1900: Compiled by descendant Hwan Ik (煥翼, ??) at the Sungyang Sŏwŏn 崧陽書院, primarily based on the Yŏngjo (英祖 r. 1735–1776) period edition, supplemented by materials from the Yŏngchŏn edition and additional records.

More information about the various editions is here in Korean.

The edition held by the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin contains a preface written by Song Si‑yŏl. It is presumably the Bonghwa Print Edition or a later one.

Collected works of P’oŭn: A preface written by Song Si‑yŏl. – SBB-PK:. Libri cor. 27, image 10

The Yaŭn sŏnsaeng ŏnhaeng sŭbyu 冶隱先生言行拾遺 (Anecdotes and the Words and Deeds of Master Yaŭn) housed in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin is another exemplary Munjip that illuminates the scholarly and literary culture of the Chosŏn dynasty. This collection, dedicated to the works and legacy of Kil Chae 吉再 (1353–1419), known by his pen name Yaŭn 冶隱, compiles poetry and prose that span his life and recollections noted by later generations. Kil Chae’s life and works were first chronicled in 1573, originally under the title Yaŭn Sŏnsaeng Haengnok 冶隱先生行錄 (Chronicles of Master Yaŭn). Over time, this initial compilation underwent several revisions and augmentations. By 1615, his sixth‑generation descendants expanded the work to include various royal sacrificial texts and texts for veneration and rituals. They re-titled it to Yaŭn sŏnsaeng ŏnhaeng sŭbyu and released it as a three‑volume, one‑book edition with a postscript by Chang Hyŏn-Kwang (張顯光, 1554–1637). The 1858 edition represents further efforts by his descendants to honour Kil Chae’s legacy. This edition was proofread by Song Nae‑hee (宋來熙, 1791–1867) and includes a continuation collection that compiled new writings and poems by Kil Chae, alongside excerpts from various documents and poems in praise of him penned by later generations.

Preface to the Anecdotes and the Words and Deeds of Master Yaŭn. – SBB-PK: Libri cor. 26, image 20

In addition to the Korean manuscripts I have presented, I recommend further exploration of the Library’s catalogue and CrossAsia database. Moreover, the East Asia Department has recently acquired the posthumous collection of the late Professor Hans-Jürgen Zaborowski (1948–2021), which contains approximately 500 pre-modern Korean manuscripts. These manuscripts are currently in the process of being catalogued. It will be intriguing to see what unique treasures the collection reveals. For more information on the Zaborowski collection, please contact the subject specialist for Korean Studies at the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin Jing Hu at Jing.Hu@sbb.spk-berlin.de.

With fellow koreanist Ms Hu Jing from the Korea section of the East Asia Department of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin.. – Photo: Lukáš Kubík

Further reading:

-

- Glomb, Vladimír, Eun-Jeung Lee, and Martin Gehlmann, eds. Confucian Academies in East Asia. Science and Religion in East Asia, volume 3. Leiden ; Boston: Brill, 2020.

- Kim, Jungwon. “Archives, Archival Practices, and the Writing of History in Premodern Korea: An Introduction.” Journal of Korean Studies 24, no. 2 (2019): 191‑199. muse.jhu.edu/article/736501.

- Reynolds, Graeme R. “Culling Archival Collections in the Koryŏ-Chosŏn Transition.” Journal of Korean Studies 24, no. 2 (2019): 225‑253. muse.jhu.edu/article/736503.

- WWoolf, D. R., Andrew Feldherr, and Grant Hardy, eds. The Oxford History of Historical Writing. Volume 2. 400‑1400; Volume 3. 1400‑1800. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2011‑2015.

Herr Lukáš Kubík, Institute of Asian Studies at the Charles University in Prague, war im Rahmen des Stipendienprogramms der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz im Jahr 2024 als Stipendiat an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Forschungsprojekt: „Maritime Confrontations with Japan in Korean Historical Sources“

Cloud & Heat

Cloud & Heat